We would like to express our very great appreciation to professor Giorgos Mitroulias for his valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of this final thesis, as supervisor.

Introduction

The idea for the Active Ground Floors project stems from two fundamental problems of Greek cities: the decay of many urban areas due to the economic crisis (e.g. vacant shops) and the timeless decay of public open spaces due to a lack of urban planning. This article initiates the theoretical discussion by highlighting the uneven development of the city and the different effects on each of its areas differently, using the scale of the neighborhood as a focal point of the city. It focuses mainly on areas that could be described as “neighborhoods in crisis” and tries to open a brief dialogue on how urban planning intervenes in these cases, based on specific criteria (upgrading the urban environment or bettering the lives of residents). The Greek city is then described by giving a brief overview of urban evolution but also of the problems it faces today, which are directly related to the way urbanization that has taken place in Greece, i.e. the absence of urban planning. This overview highlights the need that exists today, both in the area we studied and in Greek cities in general, to create new public spaces, such as “urban commons”, in an oppressive and increasingly degraded urban environment.

In the next section, the presentation of the project begins with an initial reference to the study area, a neighborhood that in recent years has been described by residents as a degraded neighborhood in the center of Thessaloniki. The decline is equally reflected in the urban environment, as the effects of the economic crisis have led to a shrinkage in commercial activity and the abandonment of ground floor stores. At the same time, through on-site research, we found that residents are excluded from social amenities, as there are no infrastructures in the area to benefit residents, such as sports facilities, libraries, etc. We then describe the central idea of the project, which is to turn ground floor stores into urban commons for the needs of the neighborhood’s residents. We analyze the program action (uses) that we propose for these spaces, how they would be designed, and who would be involved in shaping them. We then describe the steps required to transform these spaces from closed stores to active ground floors. Finally, we present the proposed design solution so that these spaces can be designed flexibly to meet different needs in their use.

Neighborhoods in crisis

Urban areas are the centers of economic and social activity, therefore they become growth poles or sometimes experience periods of recession, as they represent a constantly changing environment. The development or crisis experienced by the urban environment is not evenly distributed throughout the urban fabric (Wacquant 1996, 121–39). This uneven distribution is usually expressed through social and spatial divisions within a city, sometimes accompanied by the creation of “excluded spaces” (Skifter Andersen 2018, 108–9). In many ways, urban areas have become more unequal, fragmented and less coherent. Within this fragmented urban landscape there are areas we can call “neighborhoods in crisis”, and this issue is high on the agenda for urban interventions.

Can this urban element called a “neighborhood” be defined? Is it a distinct spatial zone or an abstract notion of place? As Zwiers, Bolt, V. Ham and V. Kempen (2016) point out in their article, there is no ideal definition of the term, and many theorists have interpreted its meaning in different ways. One theoretical approach is based on the idea that every neighborhood is different for each individual person. For example, in Morris and Hess’s study1, this has to do with the distances an individual sets up around their home depending on their daily destinations. Another theory is that a neighborhood’s definition does not depend on spatial boundaries, but is rather an idea constructed through the social relationships and networks that a person created in their resindetial environment, according to Warren (1981). Neither definition is right or wrong as it is really very complex to determine the boundaries of a neighborhood, as stated by M. Zwiers et al, while focusing on the general idea that “a neighborhood is a relatively small spatial subdivision of a city or town for which a number of physical, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics can be measured” (2016).

Do neighborhoods matter in people’s lives?

Life in cities has changed dramatically since the early 1960s. Rapid urban expansion, caused by massive population resettlements, has led to a densification of the urban environment. In addition, globalization, new means of transportation, and the bigger scale of road networks to allow faster and easier mobility within cities have greatly modified the conditions of urban life over and beyond this period (Lefebvre 2007, 8). Therefore, cities began expanding with characteristically blurred boundaries and weaker centers, where “the idea of the local becomes less important than the global” (Kempen, Bolt, and Ham 2016). At the same time, many studies prove that the place-based characteristics of the local environment can negatively or positively affect the lives of people. This depends for example on the urban characteristics of the residential area they live in, the social facilities which they have access to, the presence or absence of strong social networks, criminality, etc. This shows that neighborhoods are still an important aspect for the quality of urban life (Warner and Settersten 2017).

Neighborhood decline and the economic crisis

Examples of negative development leading to the decline of a neighborhood include a gradual deterioration of the physical condition of building quality, an obvious change in the area’s population, the emergence of ghetto neighborhoods, and so on. There are many causes that contribute to these changes. As many theories indicate, these may include external factors, such as macroeconomic factors that broadly affect the regional or national economy (Kempen, Bolt, and Ham 2016). Thus, the recent economic crisis has certainly escalated the urban crisis, as increasing social inequality had obvious spatial consequences inside the cities’ environment. The exacerbated segregation, the increasing spatial concentration depending on income and other neighborhood issues demonstrate the uneven distribution of the effects of the economic crisis, especially in areas already suffering from urban degradation (Zwiers et al. 2016).

Intervention policies for neighborhood renewal

However, there are many approaches to policies and many different objectives that focus on strategic interventions to change a part of the city (urban renewal). They could be divided into different categories according to their purpose. Interventions in deprived areas of the city are the most difficult, as the causes of a neighborhood’s crisis can be very complex (Tosics 2015, 3). Moreover, many spatially oriented urban development strategies fail to reduce degradation in the most impoverished regions because they usually focus only on physical interventions in buildings or landscapes. On the contrary, in some cases urban renewal of an area can lead to gentrification and attract new target groups of residents. In this case, there are no real solutions to the problems of the deprived area, and the impoverished community of residents from that place does not enjoy the benefits of this change, as they are shunted off to other neighborhoods.

Nevertheless, placed-based policies, which focus not only on individuals but on a specific geographical unit, most often a neighborhood, form a more inclusive strategy, encompassing both physical and social regeneration measures (area-based interventions). The main objective of these interventions is to enhance the lives of the people who live there by focusing on the specific problems of the area. Methods in this case include “invasive” measures, for example demolition, new infrastructures, housing rehabilitation, etc. to achieve urban upgrading, and “soft” measures, such as promoting people’s skills, social capital and capacity building. The meaning of urban regeneration is always contradictory, depending on the approach and the change that it is going to bring, but in the area-based approach there is always a “strong link between physical interventions and their social consequences” (Tosics 2015, 4), so that a reciprocal relationship is essential for an effective outcome.

The process of urbanization in Greek cities

Urban evolution of Greek cities

In the 1950s and 1960s, Greece experienced tremendous economic development and extensive industrialization, resulting in a major population shift from small settlements to growing urban centers. Under these conditions and during this period, intensive internal migration was mainly concentrated in the two largest metropolitan areas, Athens and Thessaloniki. This rapid population growth created a need for new land and housing. Thus, the major Greek cities began to expand very rapidly during that period. However, Hastaoglou, Hadjimichalis, Kalogirou and Papamichos stress that this urban development was “the outcome of irregular, ad hoc intervention rather than that of coherent urban policy measures” (1987, 155). The main problematic notion was that urban growth and morphology were not under the control of the State.

Moreover, they pointed three conditions that played an important role in shaping the contemporary Greek urban fabric: - Urban land was fragmented into small parcels owned by private owners. - There was no legislation concerning land use regulations and as a result all parts of the urban area developed with mixed land uses. - The building code contained many loopholes and consequently big part of the plots were constructed and high-rise apartment blocks started to define the new image of the city (Hastaoglou et al. 1987, 160).

Under these circumstances, the social access to housing of that period followed two frameworks, the “afthereta” housing model and “antiparochi” procedure. The “afthereta” model encompasses the houses that were built illegally at that time, mainly in the periphery of urban centers (Hastaoglou et al. 1987, 163). The “antiparochi” procedure as B. Ioannou and K. Serraos indicate, is “an institutional directive based on a deal between small property owner and constructor, according to which, the first offers his land, while the second constructs the building on his own expenditure and care, obliged, in exchange, to transfer a part of the building to the land owner” (2005, 1488).

Main characteristics of the contemporary Greek urban space

Shortage of open spaces for public use

The norm of this informal urban planning was extensive land exploitation and big-scale construction in most parts of the urban land. There was no institutional framework for a long-term, foreseeing urban planning that would accommodate or even envisage the creation of public open spaces (Arabantinos 2007, 120). This lack of open spaces led to serious problems as well as detrimental effects on urban life.

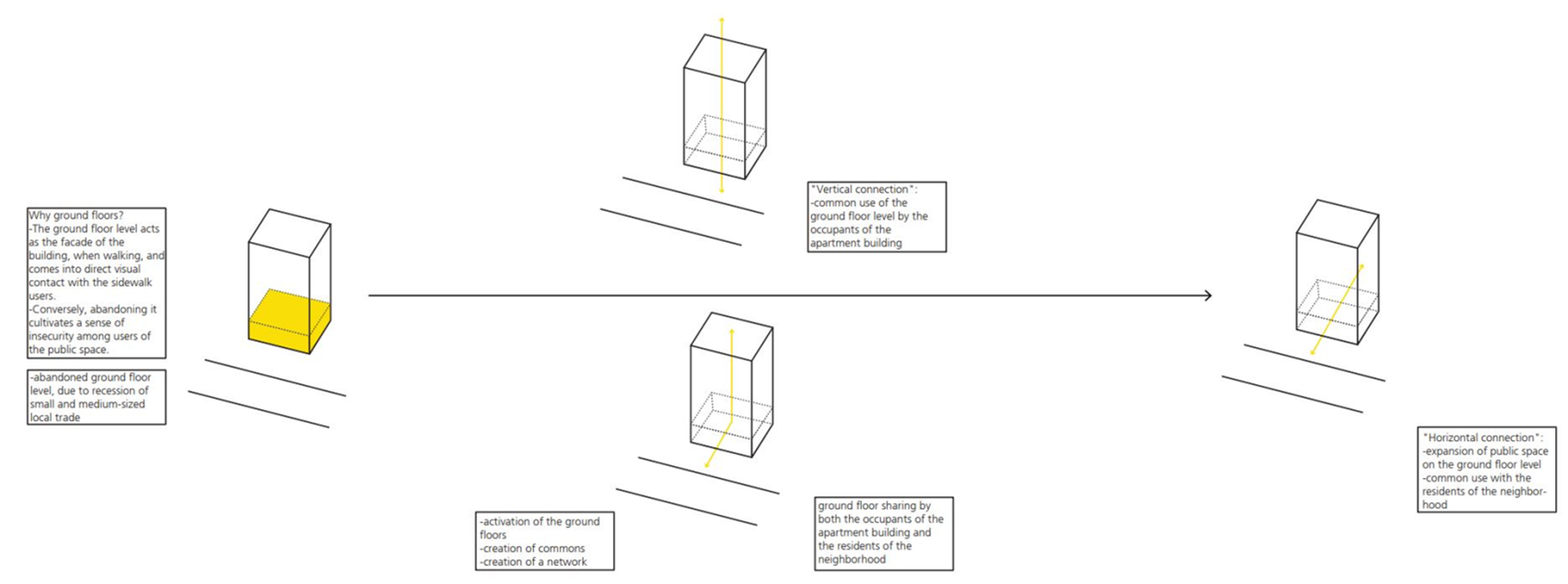

Disarticulation of scales

Finally, the main aesthetic and functional problem of the post-war fabric of the Greek city is the disarticulation of scales. According to B. Ioannou and K. Serraos, “the sense of neighborhood as a connective element between the inhabitant and the place, is extremely weak, lacking in visible boundaries or identity and differentiation elements” (2005, 1488), resulting in urban complexes characterized by an anarchic structure and lack of hierarchy, both on an esthetic and functional level. Thus, the way urban centers are structured and spread out does not form neighborhoods or residential communities, nor does it create the conditions for sociability and communication among contemporary residents. Their synthetic elements, such as the apartment building, the street and the square, do not favor contact and interaction either vertically between the residents of the apartment building or horizontally between the residents of the same street or the users of public space.

Polykatoikia

Polykatoikia is the first multi-story apartment building that was designed at that time of early urbanization through the “antiparochi” process. It is closely related to the reinforced concrete technology that was introduced in Greece at that time. This apartment building became known with that name, and it “soon became the dominant building typology and led the massive dissemination of the modern vocabulary in the Greek city” as P. Dragonas addresses (2014, 85). This building type also has a variety of uses beyond residential, such as hosting small trade shops or spaces for work areas, most of which are located on the ground floor level of the buildings (Dragonas 2014, 90). However, since 2011, the urban environment of Athens and Thessaloniki has reflected the effects of the financial crisis and protracted economic austerity measures. In addition to the economic recession during this period, the recent transition to larger commercial zones, such as the big shopping malls being built on the outskirts of the city center, has decimated small-scale commerce and left the ground floors of polykatoikias vacant (Dragonas 2014, 95).

What is evident in the evolution of housing in the example of the typology of the Greek apartment building is the haste in design and the lack of interest in the inclusion of communal spaces that could create new scenarios for urban life. Instead, the main feature is the dense arrangement of the apartments and the steep transition from the public sphere to the private sphere without any clear element connecting the two.

Ground floor, the boundary between private housing and public space: a new ground for commons?

According to Stavros Stavridis, the entrance of a building is “the real and symbolic point of inclusion of the two worlds, the inside and the outside. It is here that the union and confrontation of these two worlds takes place” (1999, 109). It contains the concept of the space in between, not as a neutral transitional space, but as a mechanism for regulating symbolic functions.

The ground floor is the edge of the building that meets the street. It is the area you walk along as you pass through the city. It is the point of transition from the private to the public sphere. At this level of the ground floor, the boundaries are a bit more variable and rarely rigid. It is the place where activities inside the building can shift to the outside and vice versa. In addition, this acme of the building usually has an interesting relief (stairs, terrace, etc.), which offers many opportunities for rest, either standing or sitting.

Therefore, the human scale in the city has a more direct contact and perception of the ground floor than with the other floors or, in general, with the other parts of the building. The street fronts and the edges of the ground floors are the ones that come into direct visual contact with the users of the city and especially with pedestrians. For Jan Gehl, the city at eye level is the most important scale for urban planning (2010, 118). Considering turning the bottom floor of the polykatoikia into a common practice would increase the flow between the buildings and make the city more open, fluid, and participatory. However, as societies function on their own particular conditions, it is not always easy for private, public and common practices to coexist. This isn’t an easy vision to put into practice.

Study area: a neighborhood in the urban district of Panagia Faneromeni

The area we focused on in our study and which data we used to develop the Active Ground Floors project is part of the Panagia Faneromeni district. This urban quarter belongs to the second municipal urban district of Thessaloniki, in the northwestern part of the city. Its location is particularly crucial, as it is situated on the fringes of the urban district of the city center and the urban district of the old city. It is essentially an axis of transition from the low-rise building of the old city to the high-rise and dense building of the downtown district.

For the purposes of the project, we defined a smaller part of this district as a field of study. This part was characterized as a “neighborhood” based on some morphological elements that we distinguished. The most decisive role in the demarcation of the study area was played by the central square of the area, the Peristeria square, and two very clear natural boundaries, the ancient Byzantine walls surrounding its eastern part and a diagonal main street axis to the west, the Pronias street. Therefore, the “neighborhood” at stake in the present study has been defined as the area encompassing the square and the eight city blocks that surround it.

In this urban section are gathered all the pathogens of the Greek cities, previously analyzed. The problem lies more in the abandonment of private property and the absence of social policies or services, rather than in the quality of the public space, although signs of neglect are evident. The area is characterized by intense urban degradation (lack of public spaces, change in the character of the neighborhood), economic decay (inactive retail, eateries and cafes) and vacant non-working spaces on the ground floor level. According to information obtained from the geospatial service system of the Municipality of Thessaloniki, the infrastructure for children facilities, for example, is limited to two playgrounds in the whole area of Faneromeni, while at the same time there are no public areas for sports facilities (indoor gyms or outdoor courts)2. As for the presence of green spaces in the area, we refer to the planted part that follows the western part of the city walls, which remains abandoned and unused to this day due to ownership issues and negligence of the municipality.

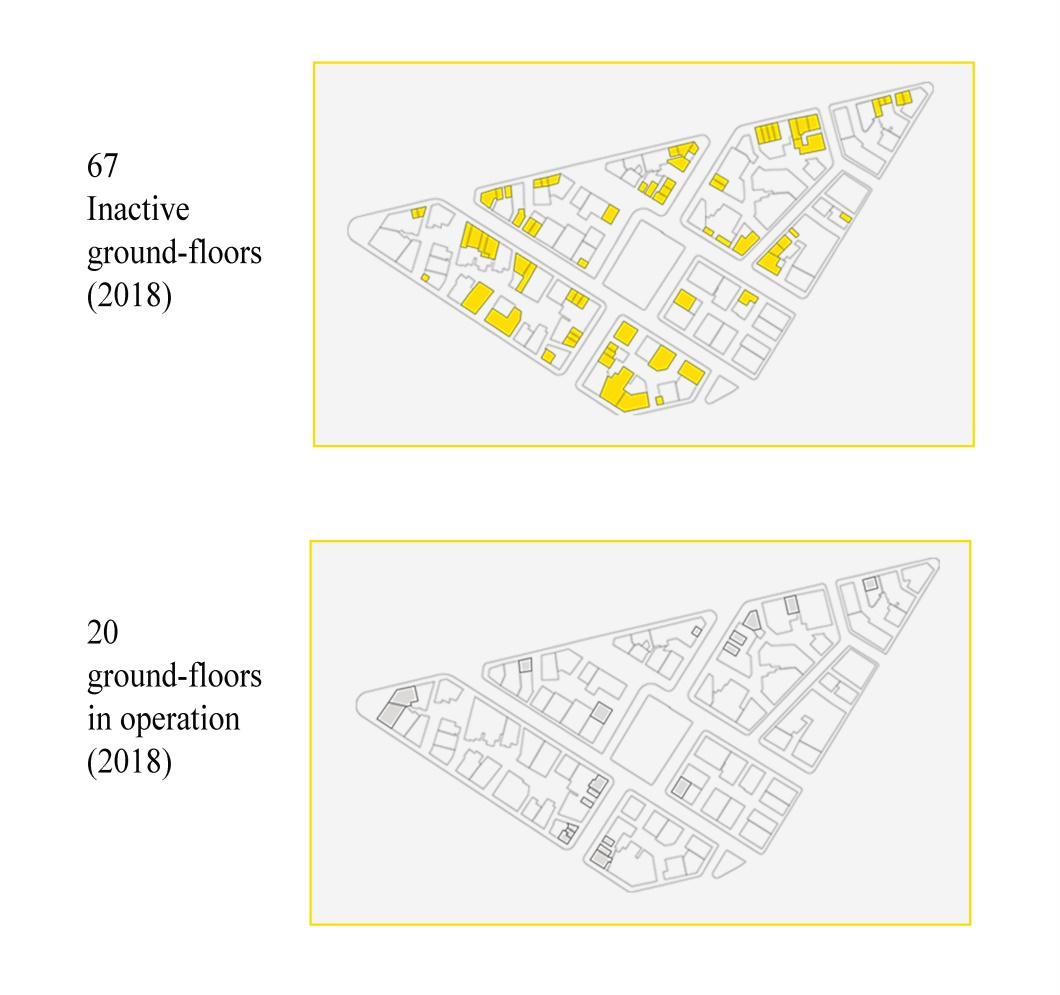

Moreover, the economic crisis has influenced the decline of this neighborhood over the past two decades. As experienced by the residents’ testimonies, we have concluded that since the onset of the crisis, a gradual negative development had started, affecting many different physical, social, and economic aspects of the area. One of these aspects was the increasing recession of small and medium sized local businesses during this period. This led to a gradual increase in business closures and the emergence of a large building vacancy. As a result, the ground floor became a “dead zone”, which had a significant impact on the decline of the physical urban environment of the neighborhood, in addition to the economic and social impacts. As of October 2018, there were 67 inactive businesses in this 8-block radius and only 20 were operating3.

One of the most interesting elements of the area, however, is its rich human geography. Since the first phase of its inclusion in the urban plan, this area hosted refugees and immigrants of different nationalities, such as Greeks from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace, Jews, Bulgarians, etc. in the early times of the previous century (Mazower 2005). Today, this heritage of the neighborhood’s character is still the same, as many new residents of the city coming from Middle East and North Africa chose to live in that part of the city.

The project

The Active Ground Floors project sought to create a program of social and physical regeneration for the study area, through the temporary activation of inactive ground floor stores and their conversion into urban commons. To achieve this, we conducted a thorough research about the ways in which a property could be temporarily made over. Consequently, a protocol-contract for the implementation of the program was built.

At the same time, focusing on the non-profit character of the project and the intention to strengthen the sense of common space in a building or a neighborhood, we simultaneously proposed a way of organizing and managing the spaces by the users themselves. The functions and uses that will take place on Active Ground Floors result from the needs, desires and initiatives of the users, who were asked to take part in the final program of activities.

Aims of the project

The Active Ground Floors project is not only aimed at improving the physical structure of the abandoned ground levels of buildings but its main objective is to focus on more integrated policies and measures to improve the social and economic aspects. Through the active participation of the residents in the planning and implementation processes, changes can be made that improve both the urban environment and the daily life of the residents of the area.

Through the activation of the abandoned stores, the city at eye level will become more lively and friendly while the ambulation will become more comfortable and safer. At the same time, the introduction of a new concept for the ground floor might gradually modify the perception of the typical construction model of a block of flats to include common spaces into it.

As far as the social aspects are concerned, one of the main objectives is to create a new reality in the neighborhood, involving residents of the apartment building but also people from the neighborhood. This can be very effective in the reversal of the prevailing social relations and the bonding between people of different culture, age, sex, class, etc. In addition, effectively educating the people who live there and are involved in the ideas of participation and self-organization can allow them to collectively take an active role. Through this, an actual improvement in all aspects of their everyday lives can take place.

Concerning the economic revitalization, it will affect both the owners of the stores and the residents that will get involved. On the one hand, the maintenance and the renewal of the stores will be a big relief for the owners. After the end of the project period, the stores will be functional again. On the other hand, the knowledge and skills that all the involved members will acquire, in combination with the network of people that will be created, can have a significant contribution in the alleviation of poverty.

Program of activities

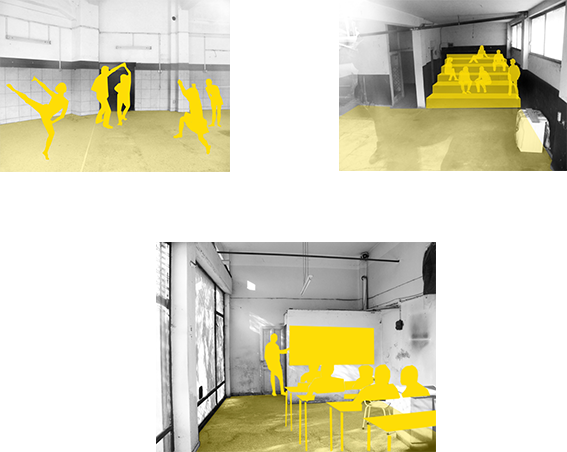

In order to avoid any for-profit activity, a charter concerning the activities that may take place in these areas has been composed. These activities are divided into two main areas, one is reserved to developing ideas such as public exchange and participation, while the other concerns educational and recreational activities. In more detail:

The axis of the development of ideas aims at initiating relations between inhabitants and cultivating a feeling of community. This is attempted by converting the ground floors into communal spaces for the tenants of the apartment buildings, but also for the neighborhood as a whole. The operation of these spaces is based on the spontaneous action of the residents themselves, who can use these spaces as meeting places while always observing the basic principles and terms of the program.

On the other hand, the axis of educational and recreational activities concerns more organized actions and is approached with two methods, the creation of a knowledge and skills exchanging network and the action that the supervisors will organize. More specifically:

Knowledge and skills exchange network

In this case, we propose the creation of an online platform that will be supportive and organizational throughout the development of the project. In this way, everyone will have the opportunity to participate in a network for the exchange of knowledge and skills, either as a teacher or as an apprentice. Neither a college degree nor an academic background is required to participate in the project. Instead, it is based on the principles of “open access”, which means that anyone can potentially teach, regardless of whether their knowledge comes from academia or from personal research, experience and practice.

This platform will enable access to knowledge for everyone, regardless of financial status, nationality or cognitive background. Therefore, those who cannot afford to pay for lessons, for their children or themselves, for activities such as dancing, learning musical instruments or others will be able to fulfill their needs and desires through it.

Through this electronic platform, each member who is interested will be able to register to the course that they intend to provide or the action that they are interested in coordinating. They must then select the most suitable space, in their judgment, through the available list of “Activated Ground Floors”, and contact the space management team (all necessary contact details will be available online). Once the proposal is approved by the management team, it is entered in the list together with the other activities/courses which are offered.

This list will be posted online and updated each day, so that everyone can have access to it and follow the activities they are interested in. It is assumed that these actions can make a significant contribution to the smooth integration of immigrants in the area and the development of relations with the residents (as opposed to the current sense of fear), as well as to the development of intergenerational relations (a significant percentage of residents are middle-aged or older people). The different cultures and cognitive backgrounds of these people can be a product of fermentation and bring about significant changes in their daily lives.

Organized actions

In this case, the supervisor team makes an open call to groups with legal status (Civil Non-Profit Company, Association or other) or not (theater groups, dance groups, ensembles or other). This is the most extroverted and organized action proposed and the main goal is to bring residents in contact with activities to which they previously did not have access or to propose new ones.

Groups that are interested will be able to submit their proposal to the program supervisors who, after contacting the residents, will evaluate and secure their approval, or their rejection. The main evaluation criterion will be whether the proposed activities meet the needs of the residents and are addressed to them, as well as whether they follow at least one of the following subject areas: Entertainment, Skills development, Social inclusion and Cohesion, Exercise and health, Gender equality, Environment.

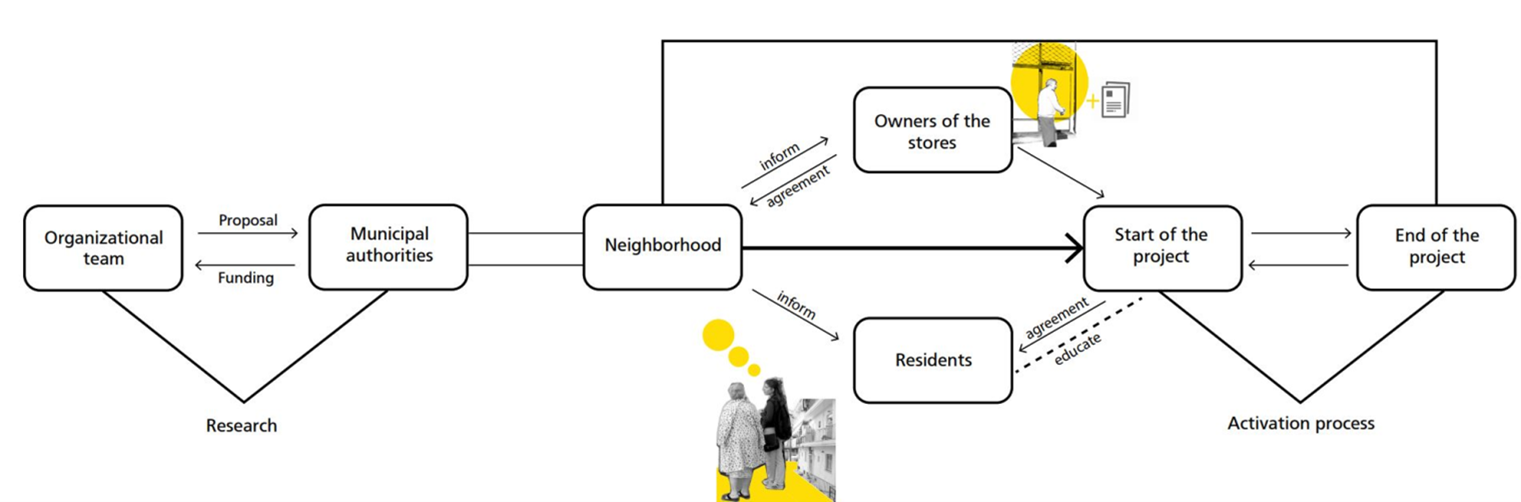

Implementation stages

What is sought is the creation of a “Bottom-Up” design process. For this reason, it is proposed to set up a group of supervisors, which, in the first phase of implementation, will assume an organizational/mediating role. In the course of its development its role will become more that of advisors. Cooperation between this group and the residents of the neighborhood, the owners of the former shops and the municipal authorities is important for the implementation of the program. The strategic design process is explained in detail in the following four steps. More specifically, the phases that have to be completed are the following:

Phase 1: Temporary make over of a property

The group of supervisors gathers all the necessary information regarding the empty stores and contacts their owners. Through this meeting, they will explain to them the “temporary make over agreement” and will formally offer them the cooperation with the project, if they accept.

According to the “temporary make over agreement” these spaces will come under the management of the supervisors and the residents, for a period of two years, without any financial burden. The benefits that the owners will gain through their participation in the program concern both the maintenance of the space, as the spaces will be cleaned, renovated and repaired, as well as the provision for their inclusion in a tax exemption regime throughout its duration.

Phase 2: Aside to the users

The supervisors invite the occupants of the respective apartment buildings in order to inform them about the program and its operation. These meetings will take the form of open meetings that we propose to be held in the empty ground floors in order to get the residents acquainted with these spaces.

If the majority of the residents of the building are willing to agree to principles, then the activation process will officially begin. However, in order for the project to evolve, it is important that the residents keep up with it, mainly in the management of these now active spaces.

Phase 3: Beginning of the activation process

After the agreement between the members is reached and before the official start of the project, there is a period of one month during which the necessary work is carried out for the preparation of the space (cleaning, renovation and repairing of the ground floors), in order to make them functional again.

Then there is a first period, lasting 6 months, which works educationally, in order to achieve the training of administrators and users on the operation of the program. This period is considered particularly important for the successful continuation and completion of the project. Through circular discussions and activities, the aim is to develop a sense of community and strengthen social cohesion.

The role of the supervisors will be advisory throughout the development of the project. The main goal, however, is that over time their role becomes less invasive and after six months the residents themselves, through participatory procedures, manage to form groups that will take over the management of the premises and will play an active role in the composition and operation of the project.

Phase 4: Closing of the project

After the 2 year period has passed and the program ends, the agreement for the temporary make over of the ground floors ceases to be valid. When this happens, the ground floor stores:

Might return to the owner in their original condition, replacing any changes made, if they request it.

In case they return to the owner, the interventions and changes in the space are maintained, if they wish it.

If the resident-users decide to continue using and managing the ground floors, an agreement must be made again between the owner and a representative group of the residents with a legal entity.

Interior design proposal

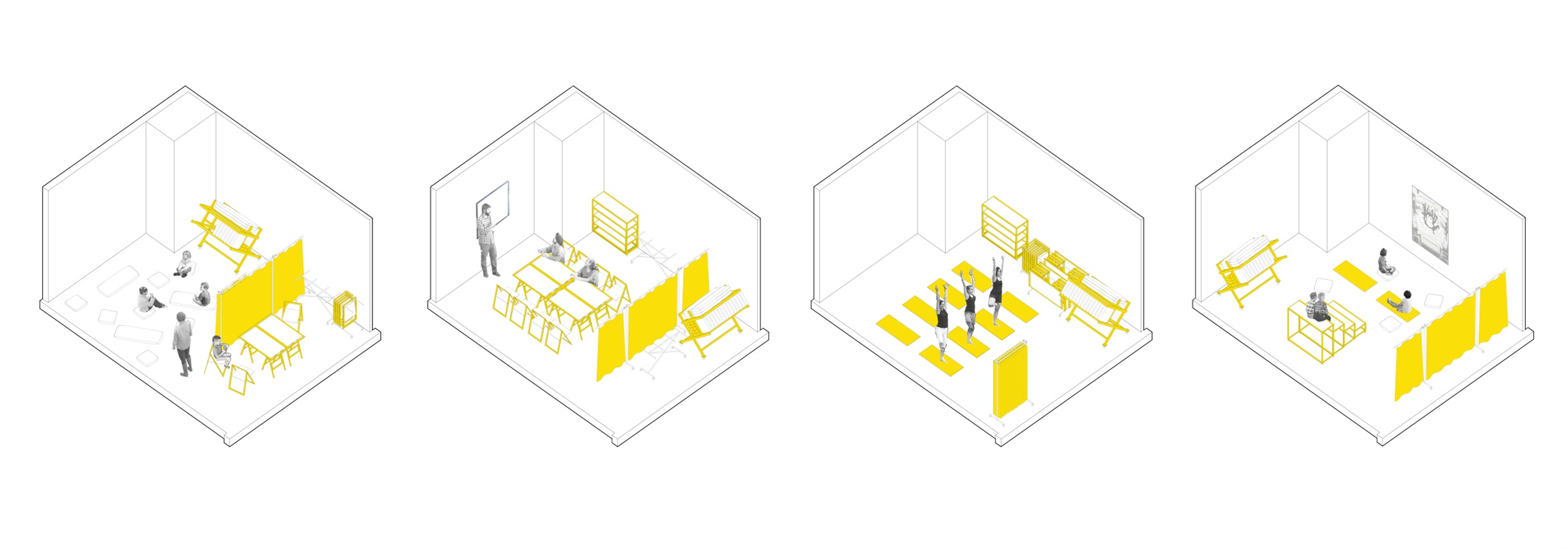

Commons cannot be designed as you cannot predict the different backgrounds and desires of the crowd that will use them. However, what can happen is the presentation of a series of possibilities in terms of needs, desires and ultimate uses they can receive. In this case, the design must be based on an open typology, based on the maximum variability and adaptability of the space.

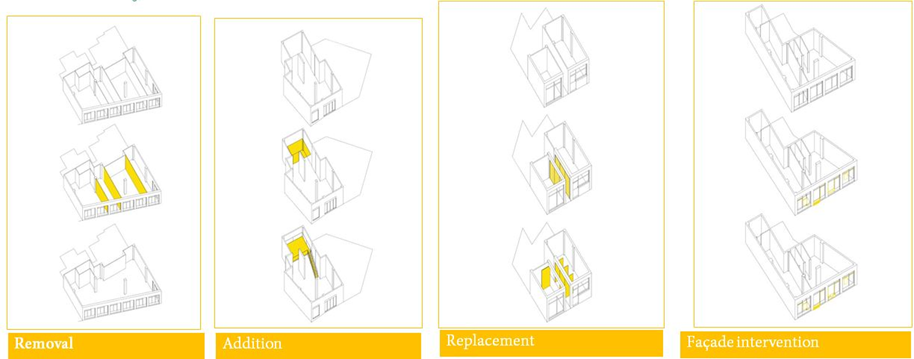

The proposed interventions in the stores are based on the particular characteristics of each one, without affecting their internal organization and based on the following three principles: removal, replacement, addition. The aim is to maintain the existing style of the space and based on its construction features, to make small interventions, which will aim to improve its functionality and can potentially be maintained after the end of the program.

The proposal of “removal” concerns neighboring stores, that can be functionally merged. This can be achieved by demolishing the intermediate partitions, with the consent of the owners, provided that the static adequacy of the building is not affected4. Respectively, the proposal of “replacement” concerns shops which are located next to the main entrance and the corridor of the apartment building, where there is the possibility of connecting them and opening a passage through the entrance corridor. This can be achieved by demolishing the partition wall and replacing it with a changing wall with rotating panels. As for the “addition”, it concerns shops that have a net internal height greater than 4.5m, with the possibility of installing a small indoor balcony metal structure, in order to increase the available space for use. The logic of “addition” includes the placement of a metal structure on the facades of all Active Ground Floors’ stores. This construction consists of cylindrical pipes and prosthetic members (bulletin board, bicycle stop, pedestrian stopping point), the shape of which depends on the dimension of each façade. This element was created in order to contribute to the visual integration of the spaces from the side of the road and to the promotion of the visual identity of the project.

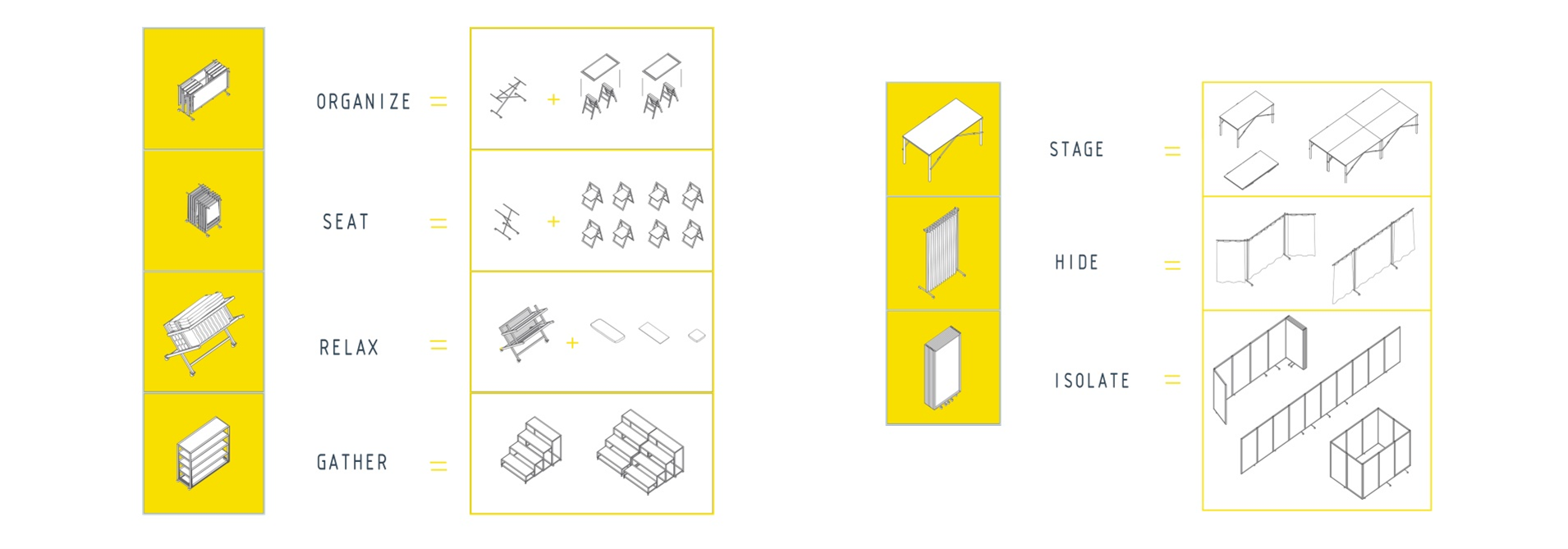

In combination with the above interventions in the stores, there is a proposal for the furniture that will accompany the actions that will take place there. In this case, the design was based on the logic of minimal infrastructure and easy storage. For this reason, the designed furniture tends to “spread” and “gather” in the space, following the principles of variability.

All these proposals for the functional transformation of the spaces and the available equipment should be published in the form of a catalog on the online platform. The selection of catalogs as a tool to present these possible transformations and possibilities of the space was judged to be optimal. It offers a range of options both in terms of interventions in the store and in terms of the choice of equipment that will frame the activities. At the same time, potential users are given the opportunity to decide on the configuration of the space themselves and to change it if necessary.

Epilogue

The Active Ground Floors project attempted to bring a new perspective to the economic and humanitarian crisis the neighborhood found itself in, but with broader social, economic, and political goals. Reusing inactive ground floors and transforming them into urban commons, it can make an important contribution to the social life of the neighborhood and improve interaction between residents. By strengthening social relations and “educating” residents in concepts such as self-management, the aim is to create a network of alternative spaces, and this is not intended to be a temporary action, but a continued and daily practice.

Bibliography

Morris, David, & Hess, Karl, “Neighborhood power: The new localism” (1975), cited in Merle Zwiers et al., “The Global Financial Crisis and Neighborhood Decline” (2016).↩︎

See http://gis.epoleodomia.gov.gr/v11/#/22.9424/40.6447/16↩︎

Field study in October 2018 for the purpose of the project.↩︎

According to the National Building Regulation of Greece, it is legal to remove walls that don’t affect the static structure of the building.↩︎

Social and land uses mixture in urban fabric

What distinguishes Greek cities from northern European cities is their social and land use mixture. This modern Fordist tradition of Western European industrial cities was based on the idea of a “clear socio-spatial division of everyday life among residence, (i.e. dormitories), work, recreation, shopping, education, all spatially separated and connected only through rapid transit and highways” (Hastaoglou et al. 1987, 165). On the other hand, the paradigm of “natural” mixed land use in Greek cities is the result of the absence of urban planning interventions. This characteristic of Greek cities resulted in the mixing of residential areas with retail areas, so that in most cities, housing, shops and services are located in the same area or even in the same building (e.g. uses accommodated in the ground floor).