Introduction

Explaining visual media through haptics seems a rather paradoxical thing to do. And yet some of the most advanced theoreticians used the sense of touch to define the new visual media of the 20th century — be it in order to approach the visual from the certainty of the tactile realm, or to examine the effect of these media beyond the merely visual perspective. László Moholy-Nagy investigated photography along with what he called “tactile culture” in the 1920s. Walter Benjamin, in the 1930s, ascribed a decisive importance to the tactile quality of film perception in comparison to its visual perception. And finally, Marshall McLuhan, after the interregnum of barbarism and the move of socio-technical utopias to a different continent, presented television as a tactile medium in the early 1960s.

Moreover, the artistic avant-garde of the first decades of the 20th century — even if they were primarily creating new ways of seeing and new ways of conceiving of the visible — also rediscovered touch as a minor yet essential sense, and tried to liberate it from its low standing in the senses’ hierarchy. The Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin coined an elegant axiom for his early organic material art: “the eye should be put under the control of touch,” he wrote on the wall of his studio (Buchloh 1984, 86f). And in Paris, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, in his manifesto Il Tattilismo of 1921, glorified the sense of touch in every way imaginable (Marinetti 2005).

1. Photography: László Moholy-Nagy and the tactility of light

The sense of touch also reached the Bauhaus, that utopian locus of avant-garde art education with its motto “Art and Technology, a New Unity.” In 1923, László Moholy-Nagy joined the Bauhaus as its youngest Meister. “I am a painter,” he declared, but — attracted to Russian Constructivism — he was more a technician, a man of the world of machines, of the media. He took over the metal workshop and the legendary preliminary course from Johannes Itten:

“By experience with material [tactile exercises], impressions are amassed […]. There is a further aim: knowledge of materials, of the possibilities in plastic handling, in tectonic application […].”1 (Moholy-Nagy 1947, 23)

Based on his observation that sensory experiences are gradually lost in today’s technical civilization, Moholy-Nagy developed his educational program so that a student “attains his own way of expression, and finds his forms. Since the majority of people build up their world at second-hand, removed from their own experience, the Institute [Bauhaus] must often fall back upon the most primitive sources […].” (Moholy-Nagy 1947, 23) For him, the preliminary course at Bauhaus was more than an educational model — it was a research program that conceived a type of sensorial-semiotic minimalism, a return to the sensory foundation of every form of expression, to basic biological elements, to their anthropological essence.

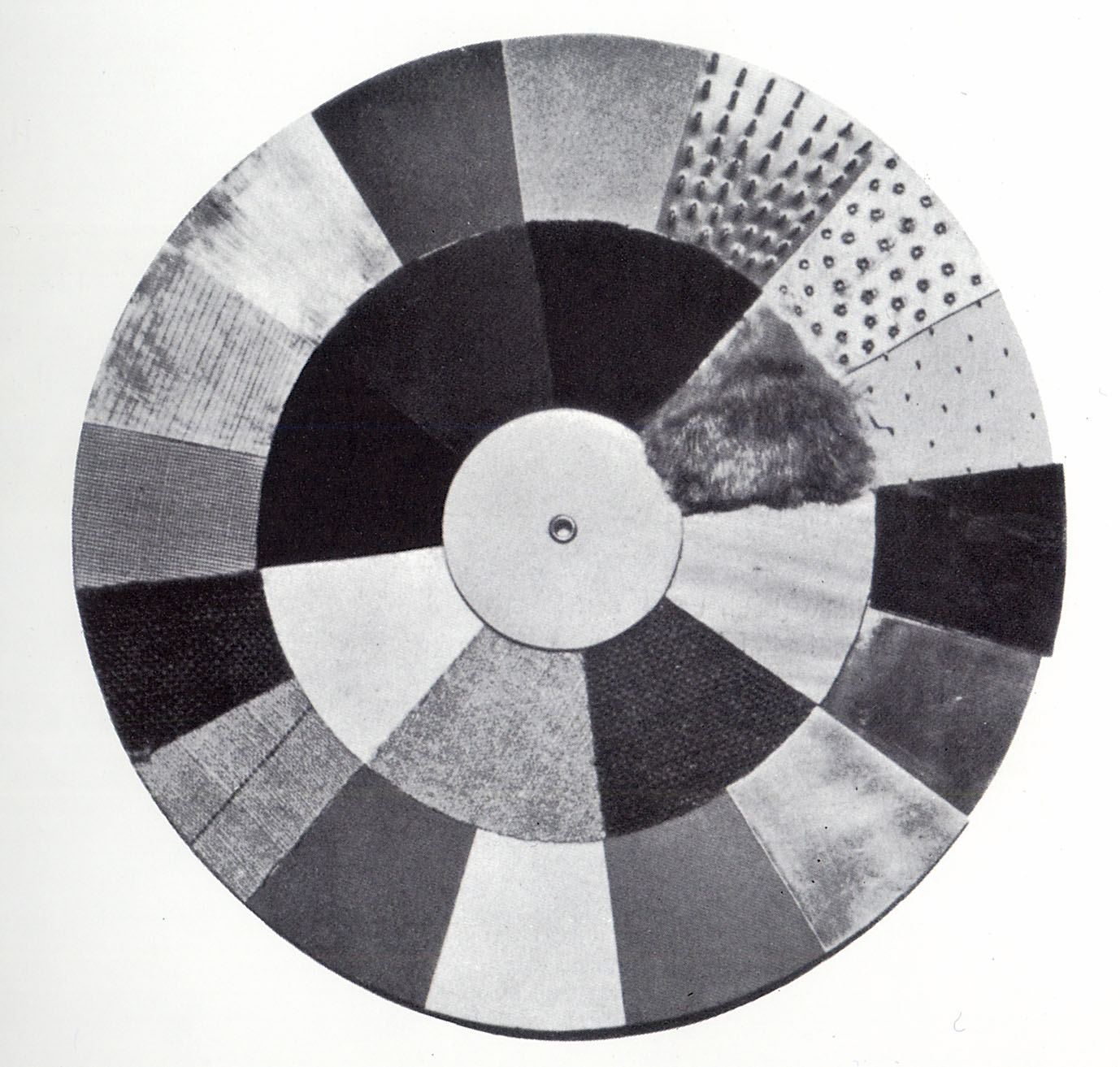

Moholy expanded on these tactile exercises, which were designed to familiarize students with different types of surfaces, “from hard to soft, smooth to rough, wet to dry.” (Moholy-Nagy 1947, 26)

This “sensory training” (Moholy-Nagy 1947, 23), using the famous tactile boards, wheels and revolving drums, was intended to introduce students to different materials and to let them explore and test new surfaces provided by various industries, such as early plastics.

Moholy was inspired by Maria Montessori who, early in her teaching, introduced children to touch exercises while blindfolded2 (Moholy-Nagy 1947, 17), and by Marinetti, the “leader of the futurists” whose manifesto on “tactilism” passionately proposes “a new kind of art that should grow out of the sense of touch.”3 (Moholy-Nagy 1947, 27)

For Moholy, however, the goal of “examining the categories of touch” at the Bauhaus was not to “teach a new art form,” but “to arouse and enrich the desire for tactile sensation and emotional expression.” (Moholy-Nagy 1947, 24) Moholy’s concept of tactility goes beyond the mere education of the senses, although this education at the Bauhaus brought superb results from the weaving studio and the metal workshop. He went further: he related tactility to the new technical media, above all photography, which he attempts to grasp using concepts relating to the sense of touch. “Praxis shows it to be true,” he writes in his book von material zu architektur, the summa of his Bauhaus teaching, published in English as The New Vision already in 1928, “that alongside immediate tactile experiences, photography — that is, an optic procedure — has fostered the culture of tactility.” (Moholy-Nagy 1968, 24) This remark can be understood as a guide to the long section of photographs that follows and constitutes the bulk of the book. He continues:

“Documentary-exact photos of material (tactile) values, their enlarged and heretofore nearly unperceived manifestation, stimulates almost anyone — not just the craftsman — to test their haptic sense.”

Photographs make us want to use our sense of touch. This is why Moholy-Nagy does not refer to the photographic reproduction’s true-to-life representation, but to an epistemological closeness of photography and tactility.4

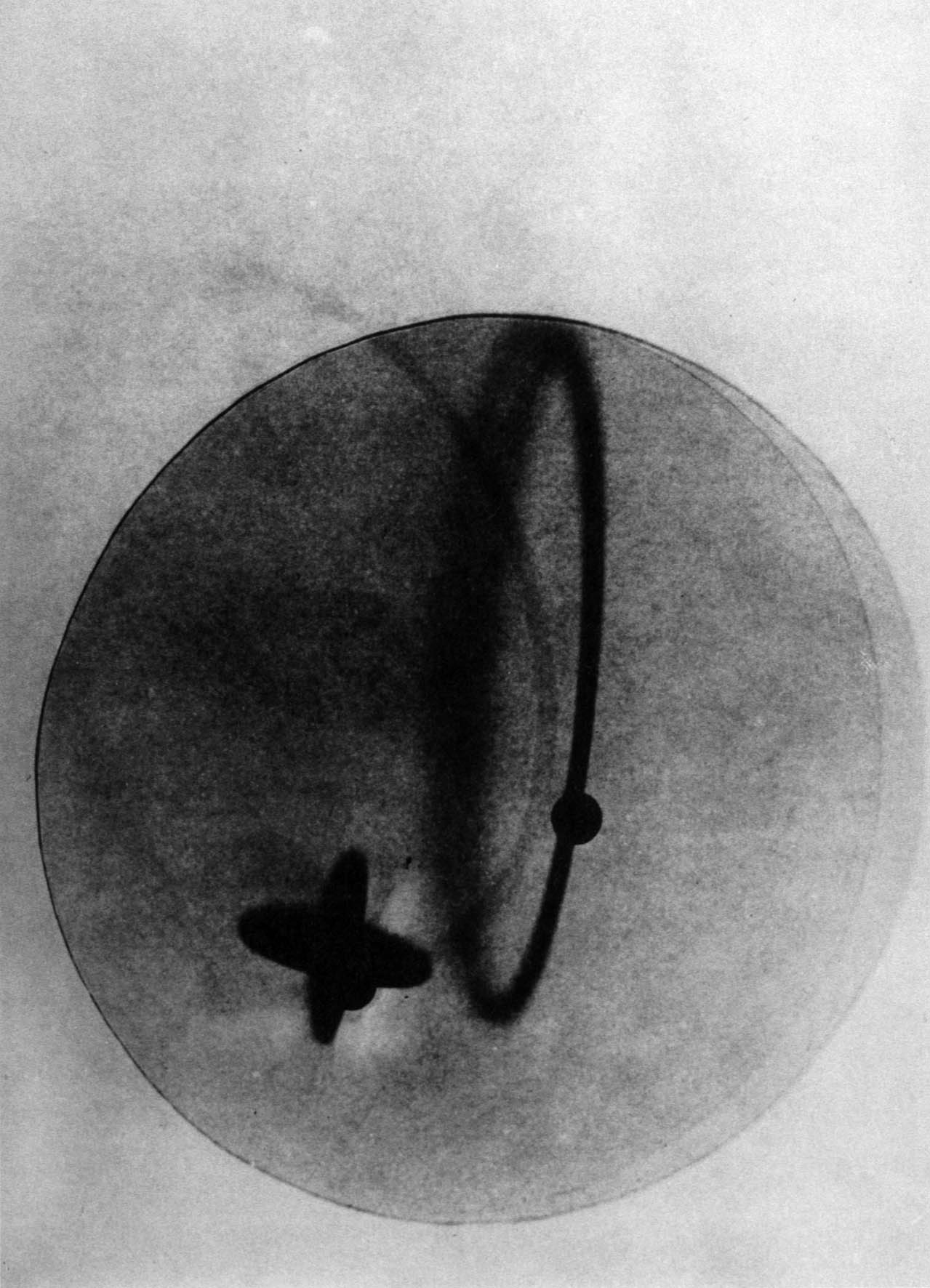

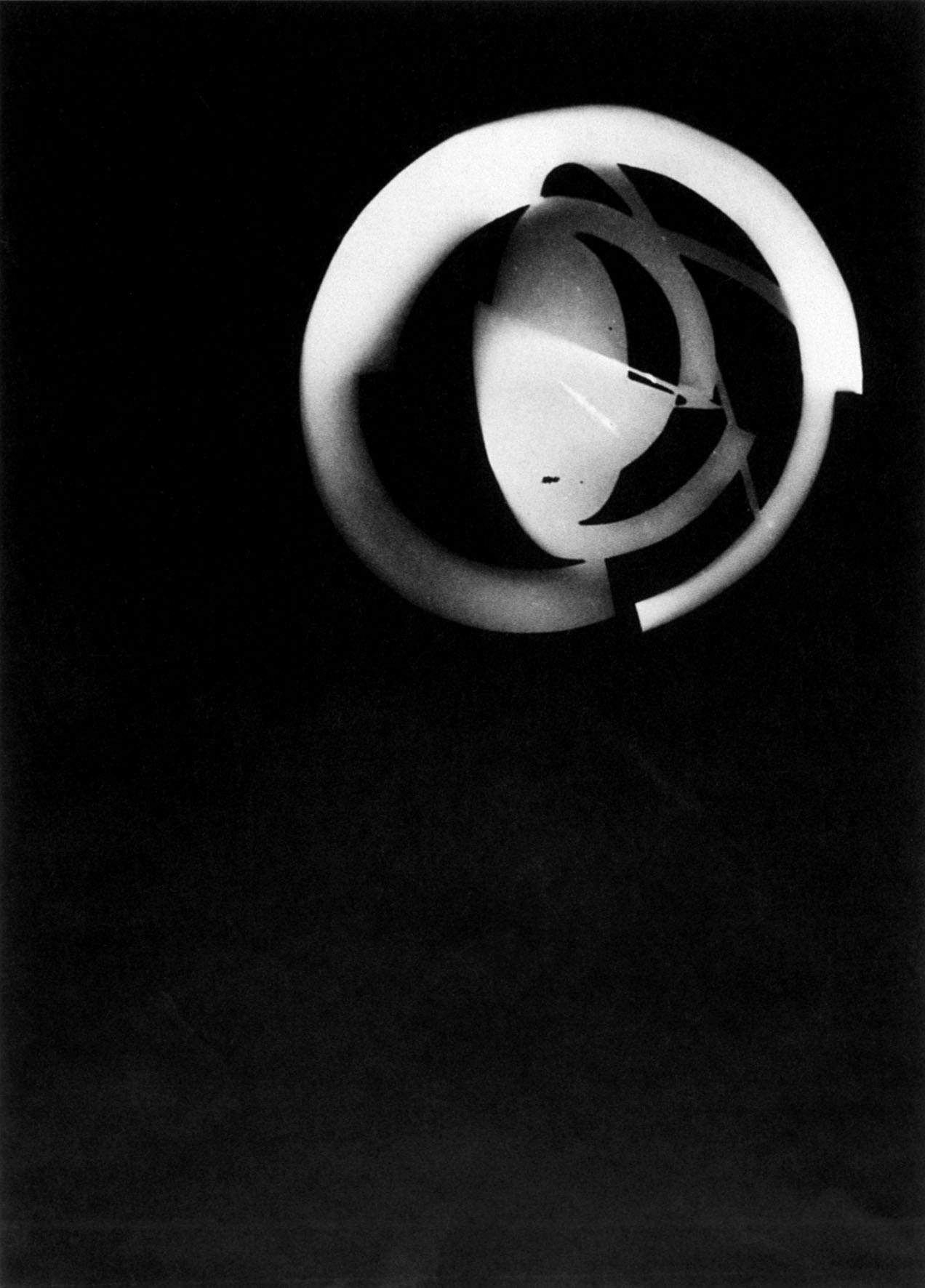

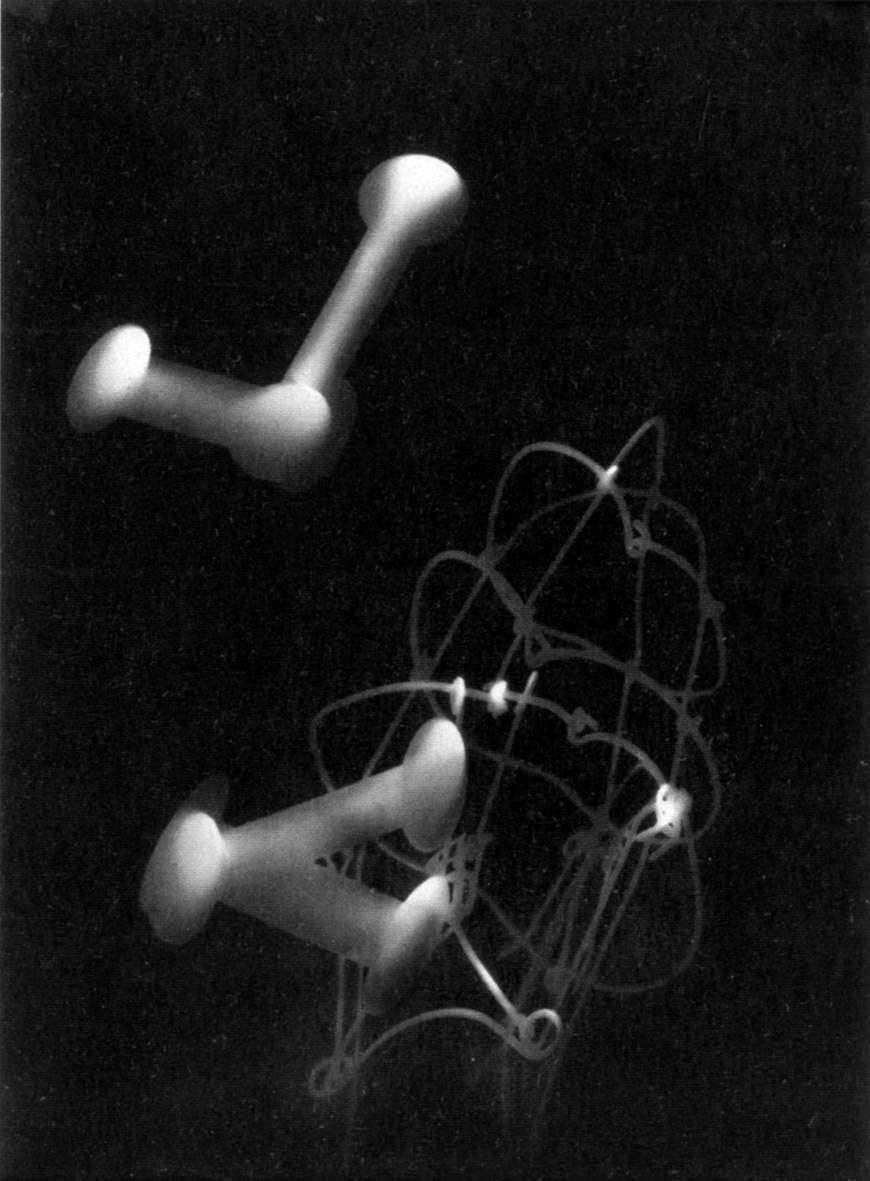

Elsewhere, Moholy-Nagy drew an even closer link between photography and the sense of touch. While experimenting with camera-less photography (Molderings 2008, 45–70), he ascribed to photography an essential tactile factor. In two articles for the international journal i 10 in Amsterdam — “Discussion of Ernst Kallai’s Article ‘Painting and Photography’” and “Photography Unparalleled” — Moholy writes about the “tangible surface,” the “infinitely subtle gradations of light and shade” and about “tangible light.” (Moholy-Nagy 1985, 85)

Moholy apparently understood photography as an experimental tactile arrangement that corresponds to the physiological model of the sense of touch: one needs a beam of light, a light-sensitive surface, be it a plate or photographic paper, and — in between — objects, either translucent or opaque. In the same way a person touches or feels something, light sweeps over the photographic paper and the object in between, scanning the arrangement. The photographic paper senses the light where the object lets it pass by and produces a chemical reaction, a “light facture” — the manner and appearance of the process of production — materiality produced through light.

Camera-less photography5 may have supported this idea, this invention of the painter, who, with his wife Lucia, the later Bauhaus photographer, began to work with photography towards the end of 1922.

For him, taking a photograph is not a means of depicting reality, but is rather a “light composition” (Moholy-Nagy 1985) which allowed him to discard the optical apparatus: although fascinated by technology, he put aside the camera so he could examine photography “directly” and reveal the processes of its production. In the chapter “Production Reproduction” in his book Painting, Photography, Film, he writes:

“If we desire a revaluation in the field of photography so that it can be used productively, we must exploit the light-sensitivity of the photographic (silver bromide) plate.”(Moholy-Nagy 1969, 31)

For this, Moholy did not need a camera:

“the essential tool of [the] photographic process is not the camera, but the light-sensitive plate or paper […].”(Moholy-Nagy 1928)

Moholy attributes tactile energy to light: light touches the photosensitive layer and inscribes its images on it. It traces this touch, indeed a quite mechanical process, which in turn makes it “tangible.” With the slogan “from pigment to light,”6 light is enthroned as a new artistic means. “This century belongs to light,”(Moholy-Nagy 1985, 85) he writes, and accordingly he continues to use the expression “tangible light” for film, the form in which photography reaches its pinnacle.

2. Film: Walter Benjamin and the surgical camera eye

For Walter Benjamin, Moholy-Nagy was an important person regarding photography, the medium that makes the “difference between technology and magic visible as a thoroughly historical variable.” (Benjamin 1999) Benjamin had read Painting, Photography, Film and certainly also some of Moholy’s articles in journals, such as in i 10, in which Benjamin had also published. But Benjamin’s transfer of the tactile to film was not inspired by Moholy, but by Alois Riegl, the Austrian art historian and curator of the imperial carpet collection at the Museum of Art and Industry in Vienna, today’s MAK (Museum of Applied Arts).

Using Riegl’s distinction between the haptical and the optical as developed in his Late Roman Art Industry7 (Riegl 1985) of 1901, Benjamin attempts to characterize how film is perceived from two perspectives in passages that have since become quite famous.

In his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,” Benjamin unfolds his argument by designating the Dadaist work of art as a missile:

“It jolted the viewer, taking on a tactile quality.”(Benjamin 2008, 39)

Benjamin then almost casually switches to a discussion on film, whose “distracting element […] is also primarily tactile, being based on successive changes of scene and focus which have a percussive effect on the spectator.”(Benjamin 2008, 39)

This idea needs developing, or rather, it needs some shoring up. Benjamin thus traces the sense of touch back to the world of optical sensations, this time relating it to architecture. “Buildings are received in a twofold manner: by use and by perception,” he writes, now providing Riegl’s terminology: “Or, better: tactilely and optically.”8 (Benjamin 2008, 40) He relates optical reception to attention and tactile reception to habit, whereby it is primarily the latter that determines the reception of architecture and even defines its optical reception. Benjamin then transfers “this form of reception shaped by architecture” (Benjamin 2008, 40) to film.

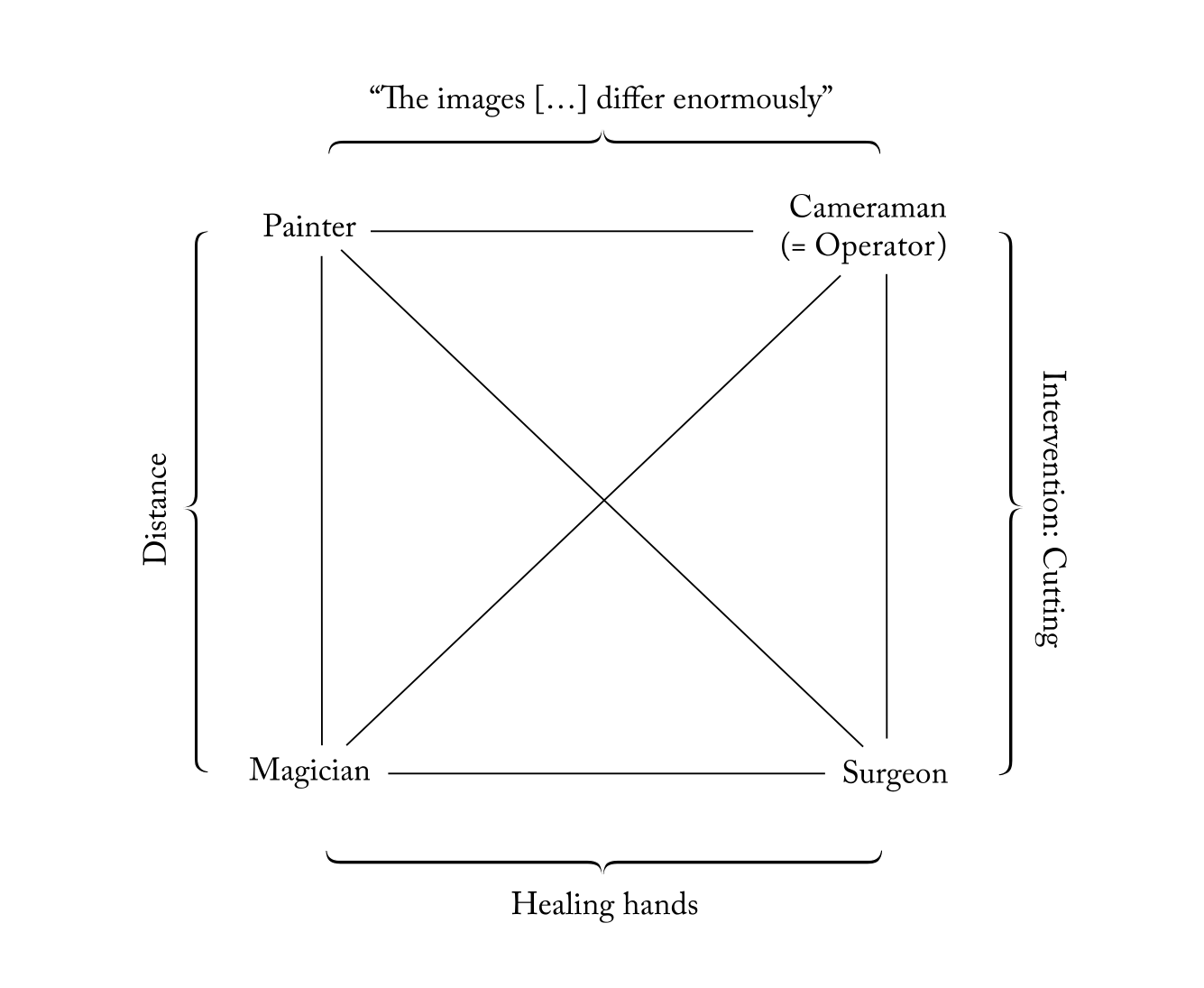

Benjamin not only places the reception of film into a tactile realm, but also its production, with the double figure of surgeon and cameraman in a constellation of opposing pairs. By drawing an analogy to the theatre, which “in principle […] includes a position from which the action on the stage cannot easily be detected as an illusion,” Benjamin defines the “illusory nature” of film as the “result of editing” (Benjamin 2008, 35) in order to contrast it — “even more instructively” — to painting.

Here the painter is compared to the figure of the magician, the camera operator to the surgeon, by using a kind of “auxiliary construction” (_Hilfskonstruktion_). The “concept of the operator,” says Benjamin, “is familiar to us from surgery.” At the time, the term “operator” was as common in German as it still is today in English and French (“camera operator” and “opérateur”). In Russian, as well, we can read in the credits of Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera, the term “operator Kaufman.”

Thus, the camera operator is compared to the surgical operator — beyond mere homonymy. Similarly, he makes the famous juxtaposition of magician and surgeon, whereby the magician “heals a sick person by a laying-on of hands,” as the surgeon heals making “an intervention in the patient.” (Benjamin 2008, 35)

Through the double opposition of magician and surgeon, corresponding to painting and film, and the faith healer’s laying-on of hands and the surgical incision, the operative cut, Benjamin creates a kind of semiotic square.

He meticulously develops his ideas around two opposing pairs, advancing the equation “Magician is to surgeon as painter is to cinematographer” (Benjamin 2008, 35) in order to draw various conclusions. For example, when he speaks of the “caution with which his [the surgeon’s] hand moves among the organs,” (Benjamin 2008, 35) he evokes the image of the cameraman resolutely searching “among the organs” of the social body. And he observes:

“The images obtained by each differ enormously. The painter’s is a total image, whereas that of the cinematographer is piecemeal, its manifold parts being assembled according to a new law.”10 (Benjamin 2008, 35)

Particularly for a patient who can no longer be healed by handling the surface, Benjamin backs the surgeon’s art: “he penetrates the patient by operating” (Benjamin 2008, 35) — just as the cameraman “penetrates deeply into its [reality’s] tissue.” (Benjamin 2008, 35)

In this way, “haptical cinema” found a second genuine figure in addition to the distracted recipient: the cameraman, who belongs to the same professional field as the surgeon. His skills combine artistic techniques and media technology. With his “surgical” camera eye, he becomes decisive for the new technically reproducible art, the art of cinematography.

3. Television

3.1 Early television: Arnheim and his marvellous tactile instrument

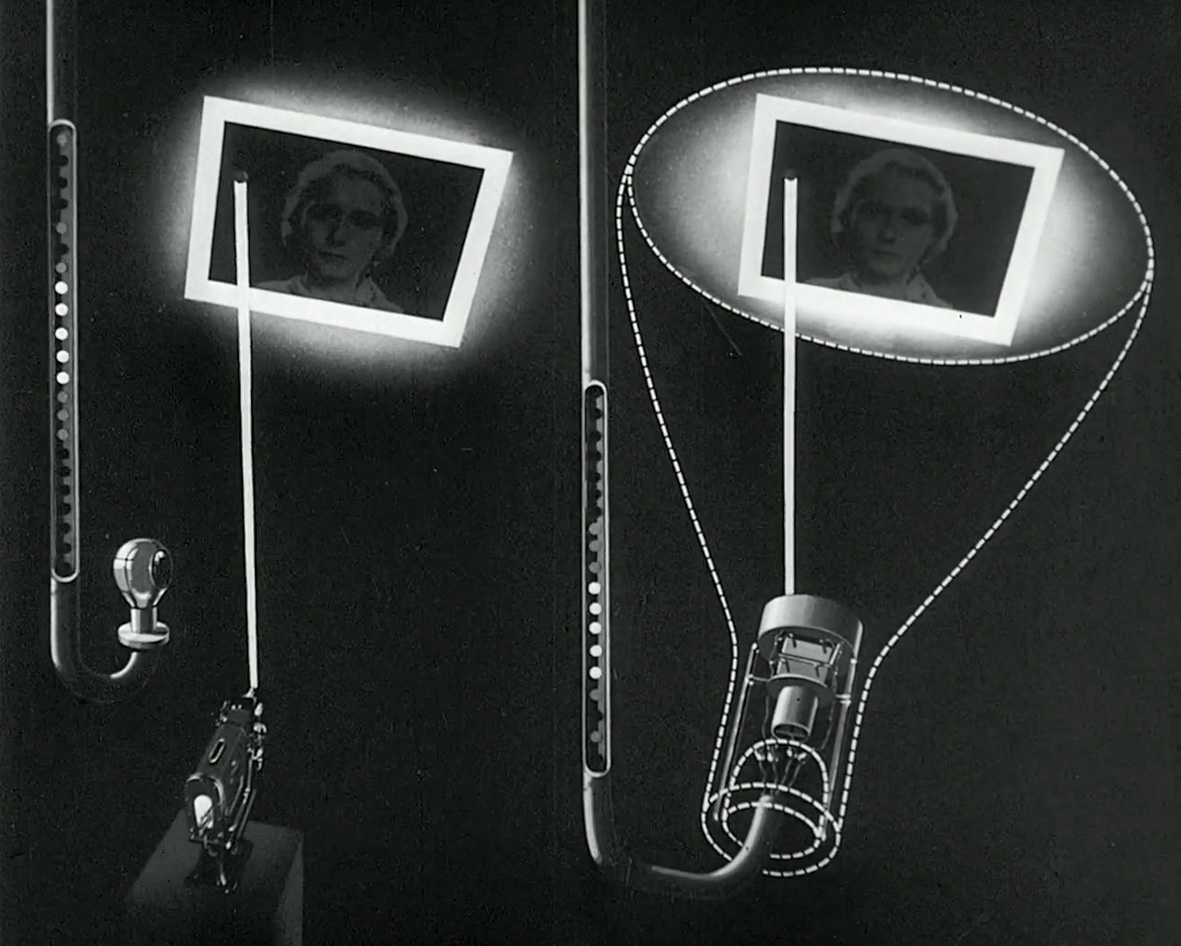

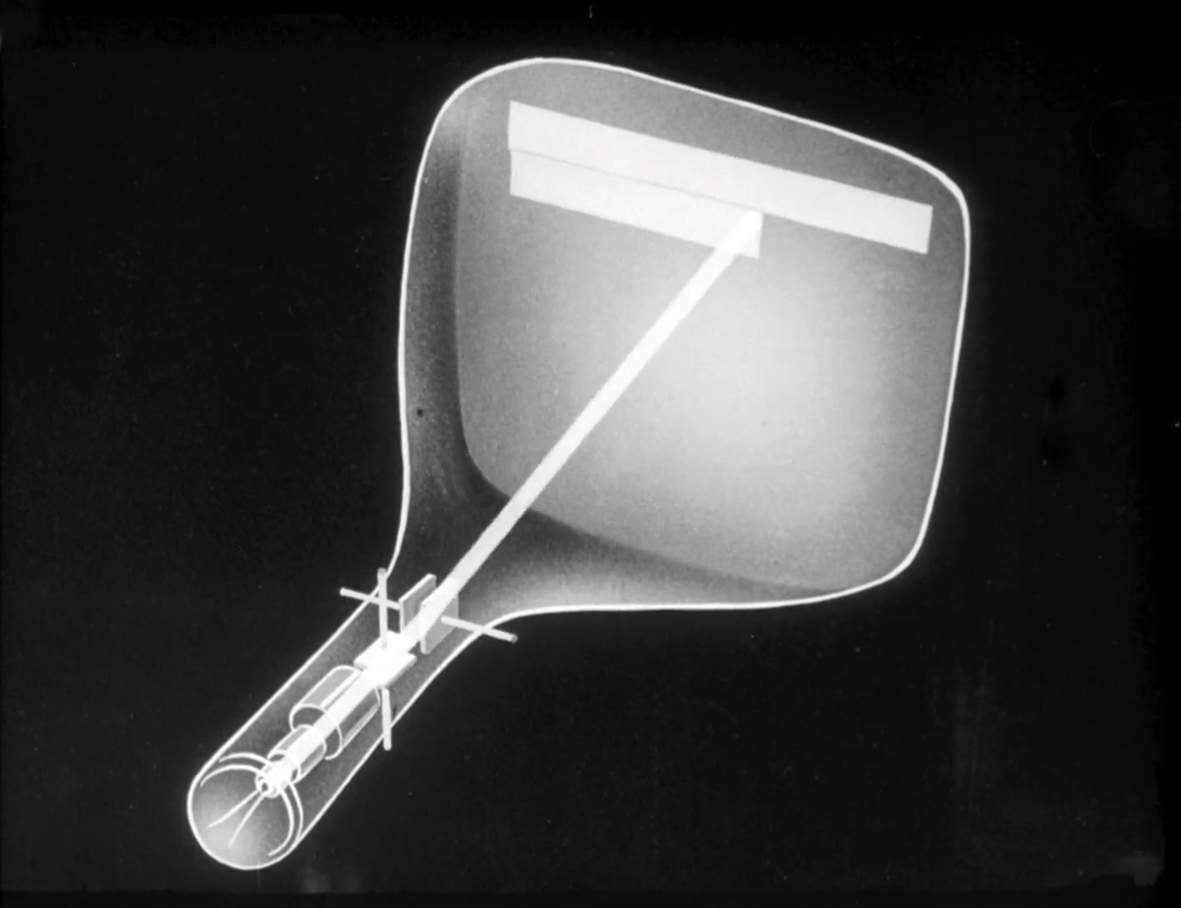

Surprisingly, television was also presented as a tactile medium during this period. Rudolf Arnheim, a young cultural editor for Ossietzky’s Weltbühne, published the book Film als Kunst in 1932, a book also read attentively by Benjamin. And in 1935, in Italian exile, Arnheim wrote an article about television with the promising title “Seeing Afar Off.” It appeared in Intercine, a journal published in Rome in five languages by the Istituto Internazionale per la Cinematografia Educativa (Wilke 1991), the pedagogical film institute of the League of Nations (Arnheim 1935). Thanks to his training in philosophy and his familiarity with perceptual psychology11, Arnheim links the new technology of image transmission with insights in sensory physiology. He examines how the seemingly “magic” (Arnheim 1935, 71) new apparatus solves the “mosaic picture” (Arnheim 1935, 72) created by our eye based on visual stimuli. To introduce the following articles in Intercine and their technical descriptions of television, the cathode ray is presented as an “index of unimaginable sensitivity” that manages to “scan the visual field, point by point, 24 times in a second.” (Arnheim 1935, 75)

“This marvellous tactile instrument,” as Arnheim called television in 1934, is the “new and sensitive organ characteristic of a refined and hurrying generation” (Arnheim 1935, 75) that allows us not only to see “what happens in the distance,” but opens up a multitude of unforeseeable consequences and possibilities. Arnheim contemplates the future developments of television, its effect on film — including even the possibility of replacing film — and predicts that it will be necessary to “compensate passivity with activity.” (Arnheim 1935, 82)

3.2 TV: Marshall McLuhan and tactual images

“Tactile instrument” and “mosaic picture” are the two striking concepts12 that then reappear in the early 1960s as appealing ideas formulated by Marshall McLuhan. In Understanding Media, he describes the television image as something amazingly tactile, distinguishable from photography and radio:

“TV is, above all, an extension of the sense of touch.” (McLuhan 1967, 356)

For McLuhan, tactility has two different meanings that continuously intersect, amalgamate and at the same time push each other forward.13 On one hand, tactility stands for the unity of the senses, or rather, the interplay of all the senses, as in the old concept of sensus communis. On the other, McLuhan is obviously referring to the electron beam of the cathode ray tube, which scans the pixels of the light grid, line by line, in rapid horizontal and vertical movements composed of an enormous number of dots lighting up and going out again. This remains invisible to the human eye, which has the impression of seeing a stable image.

McLuhan uses the technical composition of the image to describe the viewer’s perception. Television is “a ceaselessly forming contour of things limned by the scanning-finger. [… ] the image so formed has the quality of sculpture and icon, rather than of picture.” (McLuhan 1967, 334) McLuhan is aware of course, that this idea is connected to a particular state of technology, and so he adds: “Nor would ‘improved’ TV be television.”14 (McLuhan 1967, 334)

He also develops the idea of the mosaic, Arnheim’s second concept, again in contrast to film:

“The TV image is now a mosaic mesh of light and dark spots which a movie shot never is, even when the quality of the movie image is very poor.” (McLuhan 1967, 334)

Due to the lack of detail in television images resulting from this mosaic technology, the spectator is activated to complete them:

“If the medium is of high definition, participation is low. If the medium is of low intensity, the participation is high. Perhaps this is why lovers mumble so. […] the low definition of TV insures a high degree of audience involvement.” (McLuhan 1967, 340)

This is “the secret of TV’s tactile power,” as McLuhan formulated it in his famous interview with Playboy of March 1969. Here, he succeeds in explaining the core elements of his analysis concisely — and also, as expected, deliriously.15

To some degree, the mosaic is the objectification of tactility. McLuhan identifies the television image’s mosaic, precisely because it is formed from lines, a mediatic possibility to overcome the linearity of the alphabetic culture.

“The brick wall is not a mosaic form, and neither is the mosaic form a visual structure. The mosaic can be seen as dancing can, but is not structured visually; nor is it an extension of the visual power. For the mosaic is not uniform, continuous, or repetitive. It is discontinuous, skew, and nonlineal, like the tactual TV image. To the sense of touch, all things are sudden, counter, original, spare, strange.” (McLuhan 1967, 357)

Finally, McLuhan links the fragmentary nature of the mosaic and the tactile completion, the incomplete image and the sense of touch:

“The TV image requires each instant that we ‘close’ the spaces in the mesh by a convulsive sensuous participation that is profoundly kinetic and tactile, because tactility is the interplay of the senses, rather than the isolated contact of skin and object.” (McLuhan 1967, 335)

Occasionally, McLuhan gets carried away in his rhythmic prose:

“Yet ten years of TV have Europeanized even the United States, as witness its changed feelings for space and personal relations.”

He immediately explains what he means by “Europeanization,” first in the manner of an ethnologist, but then with malicious pleasure:

“There is new sensitivity to the dance, plastic arts, and architecture, as well as the demand for the small car, the paperback, sculptural hairdos and molded dress effects — to say nothing of a new concern for complex effects in cuisine and in the use of wines.” (McLuhan 1967, 336)

A few pages later, he again compares the two continents:

“Tactility is a supreme value in European life.” (McLuhan 1967, 346)

McLuhan was at home in European art history, familiar with the art historians of tactility — Wölfflin, Berenson, Panofsky, as well as Paul Klee — and he never tired of bringing them into the picture. He had read the books of Moholy-Nagy and wrote reviews about them. It is not known if he was acquainted with Benjamin’s concept of tactility. Nonetheless, in McLuhan, the lessons of the Bauhaus, the education of the senses and the re-evaluation of the sense of touch are ever-present. This is why, in Understanding Media, he writes the provoking and apodictic statement:

“TV is the Bauhaus program of design and living or the Montessori educational strategy, given total technological extension and commercial sponsorship.” (McLuhan 1967, 344)

Within the terms of full-fledged mass communication, he connects the sense of touch to basic cultural-historical transformations. McLuhan was supplied with first-hand reports on the European avant-garde and its tactile experiments by the Swiss historian of architecture Sigfried Giedion (Cavell 2003), who had also been an important source for Benjamin between the wars. Well informed, McLuhan demonstrates how television completely alters the balance of the senses.

In his essay “Inside the five sense sensorium,” which anticipates a number of concepts developed further in Understanding Media, McLuhan even applies this changed interplay of the senses to offer a transatlantic conjecture regarding the senses, ironically flipping the re-education programs of the Allied forces in post-war Europe to favour the American way of life:

“Let us consider the hypothesis that television offers a massive Bauhaus program of the re-education for North American sense life.” (McLuhan 1961, 43)

Moholy-Nagy, Benjamin, Arnheim, McLuhan: These early reflections on the tactile character of media served not only to oppose the frenetic expansion of the visual with bodily experience. They were possibly also conceived to humanize the tremendous potential of the media and tame its power by relating it to the sense of touch, the sense that, since antiquity, has represented truth, the sense that provides and guarantees authenticity.

Bibliography

Arnheim, Rudolf. 1935. “Seeing Afar Off.” Intercine 7 (2).

Arnheim, Rudolph. 1953. “David Katz: 1884‒1953.” The American Journal of Psychology 66 (4).

Arnheim, Rudolph. 1957. “A Forecast of Television.” In Film as Art. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 1999. “Little History of Photography [1931].” In Selected Writings, edited by Michael W. Jennings and et al. Vols. 2, 1927‒1934. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Benjamin, Walter. 2008. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Second Version 1939).” In The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, edited by Michael W. Jennings and et. al. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Botar, Oliver A.I. 2014. “Sensory Training.” In Sensing the Future: Moholy-Nagy, Media and the Arts (Avant-Garde Transfers 2). Zurich: Lars Müller.

Buchloh, Benjamin H. 1984. “From Faktura to Factography.” October 30.

Cavell, Richard. 2003. McLuhan in Space. A Cultural Geography. 2nd ed. Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press.

Eco, Umberto. 1986. “Cogito Interruptus.” In Travels in Hyperreality. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Greimas, Algirdas J., and Joseph Courtés. 1982. Semiotics and Language: An Analytical Dictionary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Howes, David, ed. 2005. Empire of the Senses. The Sensual Culture Reader. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Katz, David. 1989. The World of Touch. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Katz, David. 1925. Der Aufbau der Tastwelt. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth.

Marinetti, F.T. 2005. “Il Tattilismo. Manifesto Futurista, 11 Jan. 1921.” In The Book of Touch, edited by C. Classen. Oxford: Berg.

McLuhan, Eric, and Frank Zingrone, eds. 1997. Essential McLuhan. London: Routledge.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1961. “Inside the Five Sense Sensorium.” Canadian Architect 6.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1967. Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man. London: Sphere.

Moholy-Nagy, László. 1927. “Die beispiellose Fotografie.” i 10 1 (3).

Moholy-Nagy, László. 1928. “Fotografie ist Lichtgestaltung.” Bauhaus 2 (1).

Moholy-Nagy, László. 1947. The New Vision [1928] and Abstract of an Artist. 4th ed. New York: Wittenborn, Schultz.

Moholy-Nagy, László. 1968. Von Material zu Architektur [1929]. Reprint Mainz: Kupferberg.

Moholy-Nagy, László. 1969. Painting Photography Film [1925]. London: Lund Humphries.

Moholy-Nagy, László. 1985. “Photography Is Creation with Light [1928].” In Krisztina Passuth. Moholy. London: Thames & Hudson.

Moholy-Nagy, László. 1989. “Unprecedented Photography [1927].” In Photography in the Modern Era: European Documents and Critical Writings, 1913‒1940, edited by Christopher Phillips. New York: Aperture, with Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Moholy-Nagy, László. 2011. “"From Pigment to Light” and “A New Instrument of Vision".” In Telehor 1-2, Brno 1936, edited by Klemens Gruber and Oliver A.I. Botár. Vol. I. Reprint Baden: Lars Müller.

Molderings, Herbert. 2008. “László Moholy-Nagy und die Neuerfindung des Fotogramms.” In Die Moderne Der Fotografie. Hamburg: Philo.

Neusüss, Floris M., and Renate Heyne. 1990. Das Fotogramm in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts. Köln: DuMont.

Norden, Eric. 1969. “Marshall McLuhan – A Candid Conversation with the High Priest of Popcult and Metaphysician of Media.” Playboy, March.

Riegl, Alois. 1985. Late Roman Art Industry [1901]. Rome: Bretschneider.

Riegl, Alois. 1988. “Late Roman or Oriental [1902].” In German Essays on Art History: Winkelmann, Burkhardt, Panofsky, and Others, edited by Gert Schiff. New York: Continuum.

Smith, T.’ai. 2006. “Limits of the Tactile and the Optical: Bauhaus Fabric in the Frame of Photography.” Grey Room 25.

Somaini, Antonio. 2013. “‘L’oggetto attualmente più importante dell’estetica’. Benjamin, il cinema e il ‘Medium della percezione’.” Fata Morgana VII 20 (May).

Wilke, Jürgen. 1991. “Cinematography as a Medium of Communication: The Promotion of Research by the League of Nations and the Role of Rudolf Arnheim.” European Journal of Communication 6.

In the later edition (reprint, Mineola: Dover 2005), this reads: “tectonic creation.”↩

An excellent overview can be found in the chapter “Sensory Training” (Botar 2014).↩

Moholy saw to it that Marinetti’s manifesto Tattilismo was published in Hungarian in the journal MA (today): MA Vol. 7, No. 7 (1 June 1921), p. 91 . See Botar (2014) on page 26, and the illustration on page 21.↩

On the relationship between weaving and photography at the Bauhaus, especially the work of Otti Berger, see Smith (2006).↩

See the two programmatic texts “From pigment to light” and “A new instrument of vision,” (Moholy-Nagy 2011)↩

A. Somaini points out that while Benjamin adopts Riegl’s paired concept of the haptic and the optic, he inverts their historical succession (Somaini 2013).↩

Greimas’ semiotic square consists of four positions and three axes, the diagonal ones configured as relations of contradiction, the horizontal ones as relations of contrariety, and the vertical ones as relations of complementarity. See Greimas and Courtés (1982). It is important to note that a semiotic square does not represent a rigid order, but rather depicts an operative product of rotating positions that in a recursive process are continually re‑determined.↩

Arnheim compares the two mediums, as does Moholy-Nagy, repeatedly, for example in Painting, Photography, Film, “from pigment to light” as well as in other texts.↩

After coming to America, Arnheim wrote a long obituary for David Katz (1989), (Arnheim 1953).↩

The Intercine article “Seeing Afar Off” later appeared in a shorter version with the title “A Forecast of Television” as one of four new texts in Arnheim, Rudolph (1957).↩

In 1967, Umberto Eco dissects the wildly helter-skelter ideas of McLuhan in Quindici, concluding: “Read McLuhan; but then try to tell your friends what he says. Then you will be forced to choose a sequence, and you will emerge from hallucination” (1986).↩

Indeed, television today is high-definition; it cannot be distinguished from film.↩

“The secret of TV’s tactile power is that the video image is one of low intensity or definition and thus, unlike either photograph or film, offers no detailed information about specific objects but instead involves the active participation of the viewer” (Norden 1969); also in: McLuhan and Zingrone (1997), p. 235.↩