Introduction

Today, in a period of environmental awareness, the question of the right to the city is oriented towards sustainability and the repurposing of industrial leftovers from the recessions into a circular economic process. In vacant areas and abandoned buildings, an increasingly heterogeneous occupation of different practices in dimensions and temporalities fold/unfold: pop-up shops, terraces, shared workspaces, parklets, ludic spaces, common gardens or simple installations.

They all share two major common denominators: on the one hand, an opportunistic approach to occupying idle space; on the other, a limited timeframe. At the same time, however, they differ in many ways in terms of motivation and context.

The temporal framework facilitates the inclusion of new commons at a low-cost rent for communities, artists and local organisations that can benefit from these ephemeral ecosystems. In fact, the right of citizens’ participation to the city production–at the core of the Right to the city concept coined by the philosopher Henri Lefebvre in the 1960s–became fundamental to temporary urbanism1.

An operating constellation of social movements, civil organisations and citizens are involved in temporal practices to regenerate their urban environment through a commons-driven approach. This right is not individualised, but rather a common right to liberty, to urban life, to appropriation of and participation in city public life and its future imagination.

Especially after the industrial recession brought a rising number of vacant spaces, interventions based on temporal usage have proliferated widely, becoming a phenomenon to such an extent that we speak today of the temporary city and pop-up city (Baillargeon and Diaz 2020), which refer to a complementary city to traditional urban planning that does not seem to fit today’s urban complexity and social challenges. These types of intervention have also introduced a new urban vocabulary into theory using adjectives such as ephemeral, pop-up, temporal, transitional, tactical urbanism or in-betweenness.

The study particularly analyses the city of Montreal, which is moving in this direction, and it shows with several examples, initiatives and policies, how transitional urban development2 can be instilled in the urban fabric. Montreal has experienced a rapid urban transformation driven by the knowledge economy, especially in the fields of education, arts, video gaming and artificial intelligence, following the recession of manufacturing, shipping and bank sectors, which began in the 1980s and emptied its inner core. Since the 2010s, the city has become an international example for European post-industrial cities of the ability to renovate, injecting new activity into crumbling urban sectors, stimulating urban growth and reinventing the city identity. If Montreal was in the past the example of an industry-driven city, nowadays it is all about the metamorphosis of its post-industrial legacy3, and a key urban tool as part of this process is the transitional urbanism adopted in recent years by the city government in collaboration with different private-public actors.

The research firstly aims at deciphering the dynamics that underpin the process of transitory urbanism through a theoretical framework and diverse case studies that have been enacted in recent years. Secondly, the research highlights how the community and the host collaborate on the future plans of the project, their opportunities and limitations in Montreal during the temporary occupation.

The research objective is to provide guidelines for comparative studies with European industrial cities, especially concerning how an ephemeral ecosystem can link the past, present and future to achieve sustainable development that positively impacts the whole city and community health.

Post-industrial regeneration: vacant lots and their impact on mental health

The alternation between industrial development and deindustrialisation has played an important role in the production of both new urban forces and vacancy, expanding and shrinking the urban fabric. The role of manufacturing and national industry has been changing rapidly in many developed countries due to globalisation, demographic change and industrial transformations (Nefs et al. 2013). As a consequence, leading industrial hubs, especially in North America or Europe, have closed down; many buildings have become available in the city’s inner core, raising important considerations on how to retain the heritage character, take care of idle space and rebuild the urban imaginary of former industrial sites, cities and communities (Bontje 2004).

A major issue for contemporary cities is that vacancy is perceived as a problem. In fact, abandoned industrial sites have a direct or indirect effect on citizens’ health triggered by fear of crime, poor sanitation, decreasing economic and social value, deterioration and insecurity. The link between industrial urban decline and residents’ health is generally thought of on an individual level, but more and more research has shown its connection to higher-level factors such as family and community reaching the neighbourhood scale (Kruger, Reischl, and Gee 2007). This can be connected to serious diseases and even mental health disorders in residents:

Residents associate idle space with fear, causing them to stay indoors; the consequent harm to social relationships has a negative impact on social cohesion and people’s mental condition. It is also known that idle space lowers the value of adjoining real estate and deters new economic investment, thus further negatively affecting the community’s quality of life. Studies show that the physical disorder of urban space is associated with various health conditions, including cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, myocardial infarction) and mental illnesses (depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, drug abuse.) (Jin et al. 2021)

These types of places contrast with our aesthetic perception of beauty which generally correlates to an organised and uninterrupted paysage urbain, and from a functional perspective the lack and vagueness of activities stimulate a sense of insecurity. Also, from a linguistic perspective, it is interesting to mention that in English we often refer to visual pollution (eyesore) when we talk about vacancy (Baillargeon and Diaz 2020).

Starting from the 1920s, the Chicago School of Sociology has constantly highlighted the impact of neighbourhood appearance and decay on mental health:

There are several theoretical models of how neighborhood conditions could affect mental health. The environmental stress model connects aspects of the physical environment and individual mental health outcomes, as moderated by successful and unsuccessful coping. The neighborhood disorder model suggests that social incivilities (e.g., public drunkenness, street harassment) and physical incivilities (e.g., abandoned buildings, dilapidated housing) affect crime rates and fear of crime. Fear of crime could in turn impact residents’ mental health. (Kruger, Reischl, and Gee 2007)

Living in crumbling neighbourhoods can have a direct and indirect effect on our health, and abandoned sites in particular can have an impact on the place’s identity:

Boarded up and abandoned buildings reduce quality of life in an area as well as negatively affect its image. The direct economic losses related to the non-use of vacant buildings cause substantial income loss for the community. (Montréal and Ville de Montréal 2016)

On the other hand, the reclamation of the abandoned industrial sites has the potential to improve residents’ mental health (Jin et al. 2021; Kruger, Reischl, and Gee 2007) and an emerging body of research–focused especially on community health–has explored its positive effect. For instance, research conducted by the US Forest Service and the Youngstown Neighbourhood Development Corporation highlights two actions on idle spaces that have diminished crime reports: firstly, cleaning and planting by the residents, and secondly the community reuse of the space (Montréal and Ville de Montréal 2016). In Philadelphia, residents living close to reclaimed space have a lower heart rate than those living next to an empty and vacant space. Furthermore, it has been shown that planting on vacant lots, vibrant use led by local communities, and improving physical infrastructure and walkability generally help residents to feel safe and reduce criminal cases as disclosed by police departments, which enhances people’s quality of life and community’s mental health (Jin et al. 2021).

Thus, it becomes important to examine different practices and case studies of urban regeneration on former industrial sites focused primarily on the action of the neighbourhood and nearby communities.

Montreal metamorphosis: from industrial recession to creative city

Located in the province of Quebec on a 50-mile-long island along the St. Lawrence River, the city of Montreal has the second largest economy in Canada after Toronto. The metropolis has developed an interest in the international market and stands out for its strong knowledge economy [Moser, Fauveaud, and Cutts (2019)]4. As Montreal’s creative sector undergoes continuous prompt growth, the city’s many industrial remains bear witness to an economic past (Polèse and Sheamur 2009). This part analyses Montreal’s post-industrial decline and its metamorphosis from an industrial to a creative city.

Montreal mainly owes its industrial success to its strategic location. The proximity to the St. Lawrence River allowed Montreal to become Canada’s largest city in 1840, with the river acting as an industrial corridor parallel to the shoreline. In 1825, the erection of the Lachine Canal brought the river into the city and promoted the construction of new factories which created many jobs. As a result, Montreal’s population grew from 22,500 in 1825 to 90,323 in 1861, to almost 1M by 1929. However, most of the manufacturers were in the city centre, a feature attributed to Montreal’s harbour becoming the main entry route for goods in 1832 (Slack et al. 1994).

Like many other North American cities, Montreal’s manufacturing sector started to decline in the early 1900s. Despite the economic boost spawned by the First World War, the 1929 crash that caused the Great Depression led to a post-industrial shift. Local manufacturers of domestic market products such as clothes, textiles and tools could not compete with international products. It was then that Montreal undertook a cultural turn and revised its development strategies.

Manufacturers were slowly replaced by creative industries in the artistic and technological fields (Moser, Fauveaud, and Cutts 2019). The city began to specialise in sectors such as information and entertainment technology, aerospace, biosciences, telecommunications, multilingual call centres, advanced manufacturing, and a variety of emerging interdisciplinary niches. The shift from classic industrial to creativity-focused businesses has been accelerated by multiple events, such as the Montreal World’s Fair in 1967 and the Summer Olympics of 1976 (Stolarick 2005).

Between 1981 and 2011, Montreal lost around 115,000 jobs in the manufacturing industry (Montréal and Entremise 2016). Today, Montreal ranks second in North America for the biggest workforce in the “Super Creative Core” [Stolarick (2005)]5. The city is a renowned centre for visual arts, fashion, and high-tech.

The transformation of post-industrial cities into creative industries

For two decades, the evolution of the temporal-city has accelerated its presence worldwide through international media coverage and local design interventions showing a heterogeneous atlas of approaches, ways of thinking and solutions. In the case of Montreal, this urban strategy goes hand in hand with the creative economy fulfilling the same objective to link economic, technological, social and cultural development. The connection becomes even more present in a geographical context that requires constant seasonal urban adaptation to enhance everyday life and tourism.

The partnership between the city of Montreal and the French association Usines éphémères at the beginning of the 1990s is the first project which used deliberately temporary urbanism in the industrial heritage to curb deterioration and enhance the creative economy. Usines éphémères’ mission was to repurpose the urban wasteland, transforming it into creative spaces in the industrial sites of the northern segment of the Lachine Canal. In 1993 the association established Quartier éphémère, a non-profit organisation dedicated to the revalorization and rehabilitation of Montreal’s industrial heritage ensuring the transition from the former building to the new one (Baillargeon and Diaz 2020). In 1997, Quartier éphémère created the Panique au Faubourg project, which installed the works of a group of artists in vacant industries, entitled the Faubourg des Récollets.

However, in 1998 the government of Quebec, in collaboration with the city of Montreal, launched the Cité du Multimédia in the same district. This urban project, aiming to bring together IT and communication companies through tax assistance measures, eclipsed the initial intention of the Panique au Faubourg to culturally and socially reappropriate the industrial heritage of the Lachine canal.

This example demonstrates how temporary urbanism is a vector for the creative economy and a driver of social and urban innovation, used consistently by the municipality (Bishop and Williams 2012; Colomb 2012; Mould 2014). At the same time, limitations and critics of various researchers must also be presented in order to understand the long-term impact that a temporal action can have on the soul of the city and on the collectivity.

Other case studies relating to formal industrial sites, which have made use of transitory urbanism, have been developed afterwards. Fonderie Darling is an old foundry that has been converted into an art exhibition space by the organisation Quartier Éphémère. Projets Éphémères is an urban agriculture project. Designed by the University of Montreal, the planting areas give life to an unused train yard. Village au pied-du-courant, by La pépinière, is an outdoor meeting area which makes it possible to create community life around a storage wasteland. Project Young, by Entremise, is a workspace in a vacant building that acts as a laboratory for local groups. Finally, Champ des Possibles, managed by Les Amis du Champ des Possibles, is a park that enables the occupation of an abandoned industrial site.

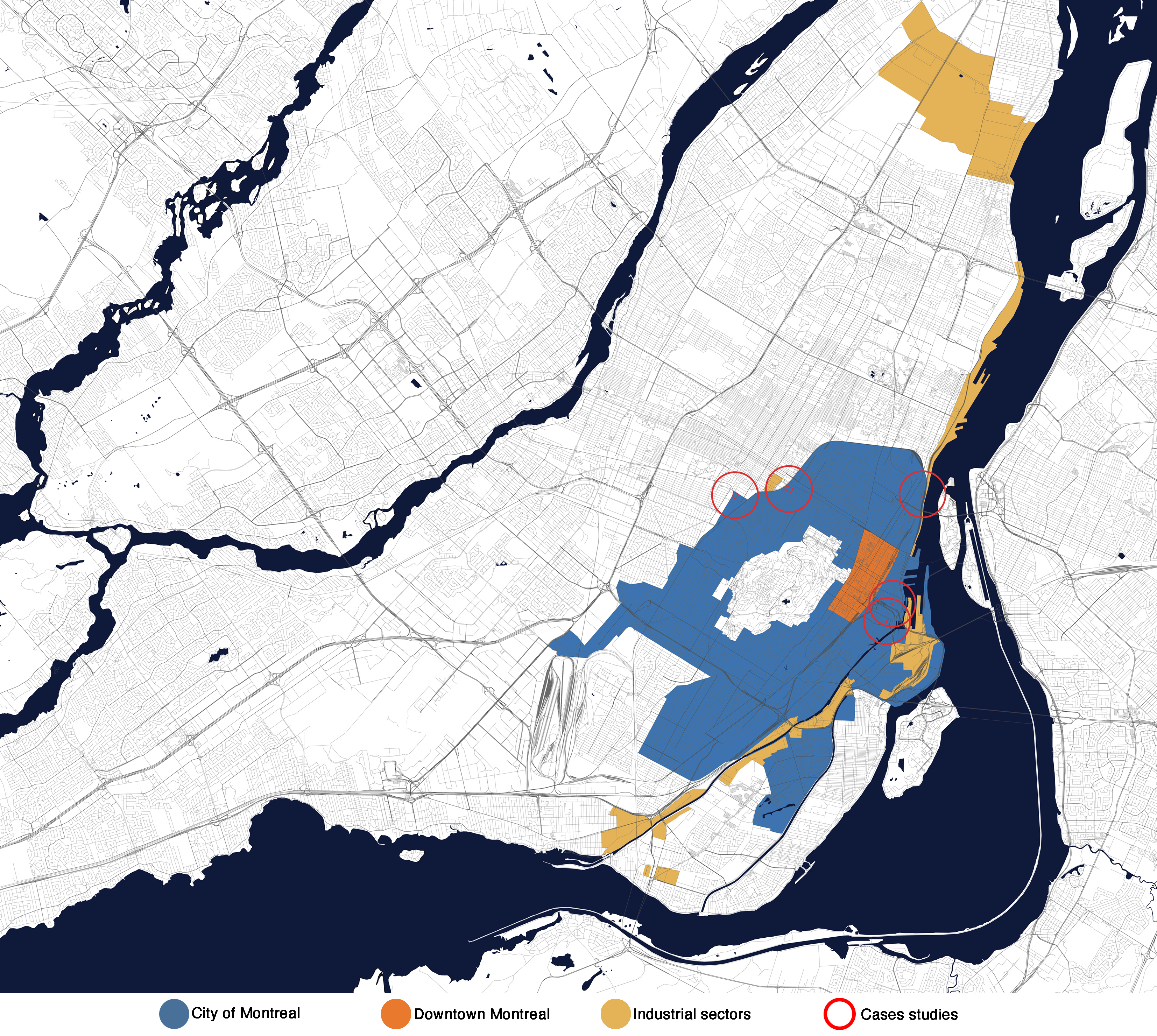

After locating all five projects on a map of Montreal, it became clear that all of them were located in the districts adjacent to the city centre. Three of them followed the shoreline and the others were situated near an old Canadian Pacific train yard. The case studies presented above are an example of a meeting between the old and the new. Montreal’s creativity allowed it to make several previously forgotten spaces functional. However, the pandemic has boosted online commerce, which has led to a lack of vacant industrial buildings. Between 2010 and 2021, the vacancy rate fell from 10.4% to only 1.4% (C. métropolitaine de Montréal 2021) and perhaps it would also be interesting to imagine how creativity could remedy this problem.

Montreal temporary urbanism in action

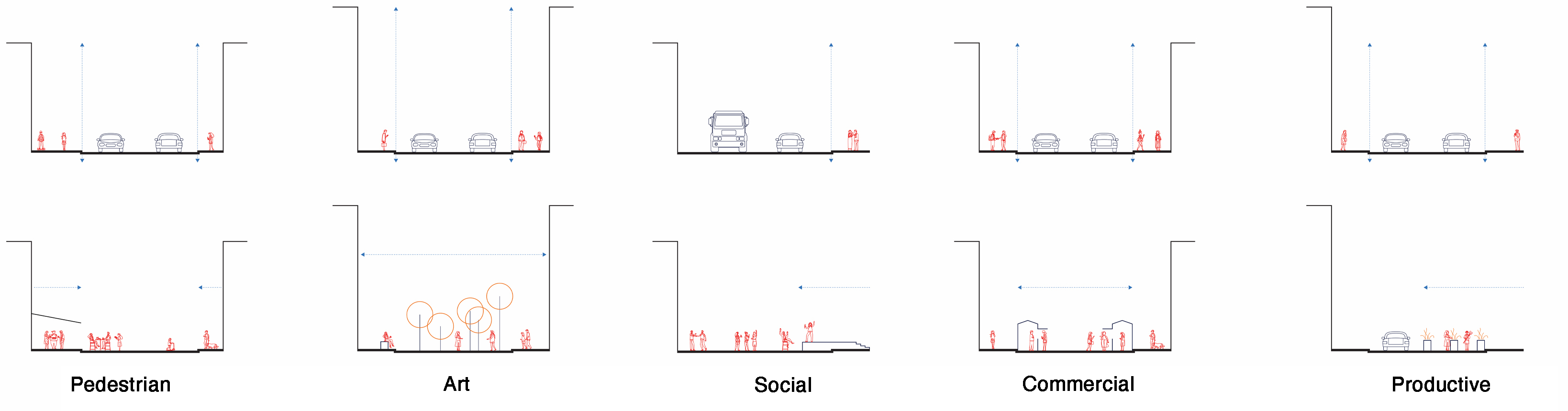

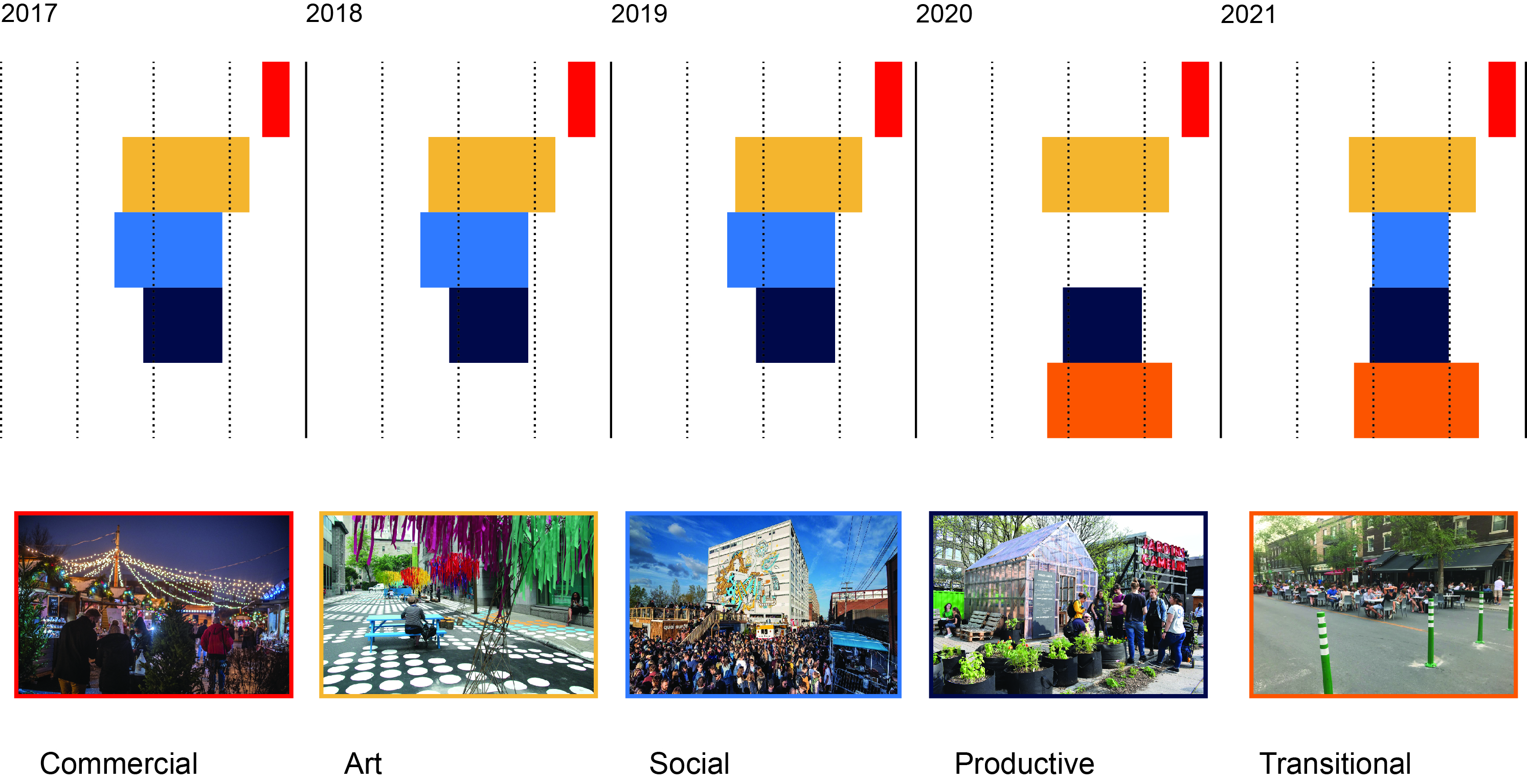

The analysis of Montreal’s current ephemeral projects made it possible to classify the city’s temporary urbanism into five different categories: social, art, commercial, productive, and shifting.

The social category refers to projects which are designed to generate interactions between users. Aire Commune by Îlot 84 is an outdoor networking and event area on an unused parking lot. The project offers free Wi-Fi and outdoor coworking spaces. Visitors can also attend lectures during the day and dance gatherings with music at night. The space usually opens in mid-May and closes in late September. Another social project is Village au pied-du-courant by La Pépinière. The project is located on a former industrial wasteland which serves as snowfall in winter. The ground is covered with sand, allowing people to meet on a beach. Playgrounds are set up for children and adults can chat around the many refreshment bars.

The art category includes all ephemeral art installations. Forêt urbaine by Paula Meijerink for the McCord Museum is a forest of steel trees through which people can walk. The artwork takes place on a closed street with furniture for visitors to rest. It offers colourful scenery that allows people to relax in a busy city centre. The installation is set up in late May and taken down in mid-October. Écho by Bertrand R. Pitt constitutes a further ephemeral art project. The installation consists of a series of landscape pictures printed on tall boards. The boards are adjacent to a sidewalk so that pedestrians can observe the pictures while on the move.

The commercial category is composed of installations that allow shopping and trading. An example of an ephemeral commercial project is the Montreal Christmas market. The market is located in a little used parking lot near the Atwater market. It opens in mid-November and closes in mid-December, giving visitors the opportunity to shop for products offered by local artisans and producers. A further temporary commercial project is Vintage Pop-Up, a shop that sells vintage items displayed by local vendors. The project takes place in a bar, with the shop opening from 12pm to 6pm when the bar is unoccupied.

The productive category encompasses ephemeral projects that generate resources. Jardins Gamelin is an outdoor event space in downtown Montreal. In addition to offering several activities, the area has public pots for urban agriculture. Small vegetable gardens offer edible plants to all. Another productive project is Projets éphémères, by the University of Montreal. This project is a community garden located in a former train yard. While waiting for the University to build a new student campus, neighbourhood residents can practice agriculture, local restaurants can grow products on site and agriculture initiation courses are given.

Finally, the shifting category includes ephemeral projects that replace cars with spaces for pedestrians. Montreal’s pedestrian streets, such as the Rue Bernard, fall into this category because they allow people to encounter others where there would normally be cars. Parklets constitute another example of this category, defined as “public seating platforms that convert curbside parking spaces into vibrant community spaces” (City Transportation Officials 2013). They represent a partnership between the city and local businesses. Parklets allow restaurants to merge with the public space. They are usually composed of a deck that incorporates seating and greenery. The design of a timeline which includes most projects of each category showed that Montreal’s temporary urbanism is mainly present during summertime, from June to September.

The pandemic allowed the city to become even more a laboratory for a thoughtful occupation of space and greatly influenced ephemeral projects during the summer of 2020 when most social activities stopped. In April 2020, nine neighbourhoods decided to set up multiple sanitary corridors and social installations were replaced by transitional areas, such as the pedestrian street. However, these new traffic arteries are more than just travel lanes, what used to be a passage lane for cars became a destination. The street acts as an extension for restaurants and local shops, which promotes local trade. Sanitary corridors are also extremely flexible, therefore, they can welcome all five categories of ephemeral projects presented above. They can host social events and art expositions; they can act as a public market and as land for food production, and as a passage lane (Montréal. 2020).

Since temporary urbanism enables the maximisation of land use while finding solutions to overcome pandemic-related problems, the opportunity to realise an ephemeral project is accessible to all. When the city of Montreal has a site to improve, whether it’s a vacant building or an unused area, the administration communicates with the Bureau du design of Montreal. The Bureau’s mission is to better develop the city while supporting local commissions. A request for commissions is sent to multidisciplinary teams of architects, designers, artists, and creators. The teams then send their proposals to the Bureau du design. Following review, a committee selects the winners and provides the means to carry out the project. Once the project is completed, it benefits the community for a limited period (V. de Montréal 2021a). In some cases, multidisciplinary teams can identify places to improve and propose a project to the city. This is what the organisation Quartier Éphémère did to revive an old foundry in Griffintown, one of Montreal’s former industrial districts.

Risks of temporary urbanism

Temporary use has already become a magical term: on the one hand, for those many creative minds who, in a world ruled by the profit maxim, are trying nevertheless to create spaces that reflect and nurture their vision of the future; and, on the other, for urban planners to whom it represents a chance for urban development. (Denton and Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung (Berlin, Germany) 2007)

This part continues the analysis of the relationship between creative economy, transitional urbanism and industrial regeneration while depicting some of the risks and limitations of this practice.

The case of Panique au Faubourg highlights the restrictions of temporary urbanism during the conception of the site’s identity. The initial aim was to forge a community and the site’s future identity, but it became instead an instrumental device to implement a formal masterplan not connected at the neighbourhood scale. Even though the project was a public success, the cultural initiative did not succeed in conveying the symbolic importance of the industrial site, leading to a project that could repurpose the building while preserving its architectural uniqueness. On the contrary, the renovation has decreased the architectural character of the old industrial site, prioritising the building’s layout for the new activities within the scope of the Cité du Multimédia (Bélanger 2011).

This project is one case of a more systematic risk. The cultural reconversion of an industrial building contributes to the creation of a brand image valued by the property developers who aim to support major operations for the district development. Firstly, the promoters can validate their role, relying on the positive impact of their action in the regeneration of industrial sites (Poitras 2002), which can mitigate problems linked to ecology, health and community. Secondly, this positive behaviour can allow them to operate in large-scale development with the approval and trust of public opinion. There is definitely an implicit instrumentalisation of tactical urbanism, from a practice able to connect the community and new available sites easily and quickly to a driver of gentrification that generates a long-term negative impact in addition to encouraging the disempowerment of the State (Mould 2014).

Another risk is the seductive power of temporal reuse that “appears to be a floating signifier capable of encompassing a wide variety of activities and of fitting a broad spectrum of urban discursive frameworks” (Ferreri 2015). Due to the financial crises, many cities in Europe and North America are adopting regimes of “austerity urbanism” (Peck, Theodore, and Brenner 2012); however, at the same time, they need to deal with necessary projects of urban revitalisation and regeneration.

In this situation, municipalities are encountering financial problems and a lack of resources to achieve a formal masterplan. Pop-up interventions and temporary uses have rapidly become the solution for the stalemate, providing quick and low-budget urban solutions where the economic priorities are lacking or are allocated elsewhere.

The lack of material resources and the proliferation of temporal projects becomes a permanent but temporal solution to try to solve deeply rooted problems. It is gradually instilling in the subjective experience of the city an increasing sense of uncertainty towards our environment and, again, community health:

Lacking material resources, it allows the celebration of precariousness and insecurity as a position of power, rather than of powerlessness, in regard to the possibility of intervening in urban dynamics and this distinction between urban space as fixed and temporary action as dynamic can be found in the unspoken assumption that temporary urban practices bring dynamism and mobility to the (allegedly static) social and built fabric of cities. In the ‘meanwhile’ discourse, space can be transformed in only one temporal direction, i.e. a trajectory of never ending urban economic and real estate development, while social, artistic or political projects of common use and re-appropriation, being an exception to this mainstream imaginary, are relegated to inhabit the space of temporariness. (Ferreri 2015)

Flexibility, temporariness, resourcefulness, and creativity are current international trends replacing more traditional architectural values and attributes in the design process, such as the Vitruvian’s idea that a project must have three main attributes: firmitas, utilitas, et venustas (“strength, utility, and beauty”). This trend should make us reflect on the implication that the proliferation of temporal practices can have on the urban imaginary of our future cities. Ultimately, the indifference to providing radical solutions for an increasing amount of social, ecological and health problems, becomes a threat to the public core of our cities and communities.

How can we more accurately connect abandoned and vacant spaces with those who need them? How can transitory urbanism become a tool to build stronger, more interconnected communities? How can temporary urbanism mitigate some of the mental health risks related to abandoned industrial sites?

Based on these premises and research questions, the second part of the study investigates how some cases found in Montreal are turning vacant industrial spaces into vibrant and thought-provoking community spaces through a commons-oriented approach. They are proposals for alternative ways to design our cities and interconnect our communities, facilitating inclusivity and connectedness via participation and collective re-imagining.

Transitional urbanism: a case study exploration

Fonderie Darling Brothers

Among the works of the Panique du Faubourg association, the Foundry of the Darling brothers is an example of how to transform temporary urbanism into a permanent project. As explained by Caroline Andrieux:

The building belonged to the City and it was in ruins. Its soil was contaminated, its windows exploded. But I told myself that one could not ask for better than such a place for artistic projects. I asked the City to lend us the building for restoration. They thought we were completely crazy, but they let us do it. (Petrowski 2015)

The proposal was to convert the building into a visual arts centre and trigger a long-term process of transforming the abandoned building. After some impediments, the proposal was submitted and the signature of a long-term lease between the Société de développement de Montréal (SDM) and the Quartier éphémère confirmed the partnership. Quartier éphémère will ultimately succeed in bringing together enough partners and resources to renovate the Fonderie Darling with the acquisition of the building in 2004. The acquisition enabled the self-sustainability of the project dedicated ultimately to artistic creation, production and dissemination.

The rehabilitation of the site unfolded in two phases. Firstly, it was carried out between 2001 and 2002 by Atelier In situ, a young architectural firm. The intervention focused on a multitude of small interventions to rehabilitate the building and its basic needs for a comfortable occupancy. From 2003 to 2006, the second phase was carried out by the architectural firm L’ŒUF, a Montreal firm focused on sustainability and place-making. The intervention created new spaces for artist ateliers and took care of the preservation of the industrial heritage memory.

Since 2007, the occupants of the Darling Foundry have occasionally taken over the corresponding section of the street and surrounding public space with temporary artistic installations, musical events, community gardens, picnic tables, or an ephemeral skatepark. This multitude of programmes activated the local neighbourhood and bound the community throughout the year. The Darling Foundry founder stated: “For me, the physical presence of the artist in the community is very important too. Artists are like philosophers. They make links in between. They create communities.”; which explained the strategy of creating proximity with the community that could be a lasting action in the future of the neighbourhood. The ultimate aim is to bring the strategy of conviviality outside the museum’s walls (Baillargeon and Diaz 2020).

Even if the actors in this project are not yet talking explicitly about transitional urbanism, the occupation strategy used here is similar. It began with a set of small-scale interventions aiming to prepare for the arrival of the project, reinforced by the support of the local community. It led to a permanent, authorised and planned occupation.

This case also shows that transitional urbanism goes beyond the ambition of occupying and upgrading a vacant building. Thanks to a strong citizen mobilisation and the continued involvement of a committed organisation, it becomes the expression of a cultural, social, and political solidarity movement between different actors who project themselves onto the future of a building and the development of a neighbourhood.

Project Young

In 2016, the government of Montreal initiated a discussion series with different actors and organisations to prepare the Heritage Action Plan (Plan d’action en patrimoine 2017-2022 de la Ville de Montréal)6. In this context, fostered by rising problematic issues of heritage management, the non-profit association Entremise was invited to participate, introducing for the first time the concept of transitional urbanism to the city of Montreal as a solution to the industrial vacancy and its rehabilitation. Entremise and the municipality organised the event “Montréal transitoire” as a new emerging concept to broaden the discussion, to get different players involved, to discuss the problems and possibilities of the practice, and to compare transitional practices in Montreal to international cases (Montréal and Entremise 2016). This is the beginning of the emerging practice of transitional urbanism in Montreal whose main slogan became “connect spaces without people to people without spaces.” The result was a shared vision of the city of Montreal, Entremise, other organisations (la fondation McConnell, la Maison de l’innovation sociale) and the community to reactivate vacant buildings while reducing the growing rate of vacancy available in downtown areas.

The first pilot project born from this vision is the rehabilitation of a hangar, owned by the city, in the Griffintown district (Autrement 2020). Twenty organisations–entrepreneurs, artists and promoters of community-based projects–have been selected to temporarily occupy 5,000 square feet of the vacant building.

The occupants were involved in a participatory design workshop with Entremise in which they jointly determined the layout and interior design to be adopted for each programme. This process gives the participants the tools to co-design and resolve issues of ownership through a practice geared towards the needs of users. Although the inclusive approach adopted to manage the building and its activities related to social connectedness, the project does not have enough impact on the neighbourhood and its future urban imaginary that is undergoing a massive gentrification process.

Projets Éphémères

A former marshalling yard in requalification is housing an integrated district developed around the new MIL Campus of the University of Montreal. The multifunctional masterplan will host the science and technology faculty plus social and community housing for a total project area of 38 hectares. The industrial infrastructure has been a fracture in the urban fabric of Montreal and a source of division between different residential neighbourhoods that were unable to communicate physically and socially and the repurposing of the site into the university campus becomes an opportunity to renew the city and its communities around.

During the phasing of the masterplan, a segment of the project where the faculty of science building is located was allotted for temporary activities between 2016-2020 under the name of Projets Éphémères. Projets Éphémères are part of a prototyping process that can be considered “slow” and which offers more leeway for exploration. The occupancy agreement is for a five-year term and a one-year term renewable for each ephemeral project.

Each year, the project’s agenda responds to the site evolution both in programmes and modifications of its physical space and accommodates new structures (i.e. the addition of a hall, exhibition spaces, projection screen, a covered terrace, planted areas, furniture) and practices (gardening, beekeeping, horticultural, educational, cultural and scientific activities) to respond to the evolution of its programming and to trigger a reflection on the space and the neighbourhood’s evolution (Cha 2020).

Slow prototyping becomes crucial to exploring the feasibility of an idea in relation to site-specific place and group of people; simultaneously, a one-year span enables the establishment of social connectedness and the communal exploration of various issues.

The character of transitional in-between place allows for collaborative and self-organised activities that engage with the surrounding context. Smets (2014) defines the realisation of temporary spaces at the contingency of three groups of actors and objectives: opportunism, activism and self-organisation. Projets Éphémères respond to these groups in a space devoted to binding the community and neighbourhoods living at the periphery of a long and transformative masterplan through assemblages of materials, fabrication and prototyping while creating a new identity of the place.

The state of in-betweenness gradually transforms the perception from a non-place to a place of imagination and hope that dissolves the traditional notion of public space as a formal and institutionalised condition into a space for collective experimentation (Cha 2020). Ultimately, as part of the long-term masterplan phase, the Ephemeral Projects on the MIL campus have contributed to transforming an unused area into a place of learning and education; to sensitising citizens to the appropriation and enhancement of urban spaces; and to bringing the community closer to scientific knowledge and the permanent project.

Guidelines

Montreal is an example of a post-industrial city that nowadays is all about the transformation and reinvention of its legacy, a player in this process being the transitional urbanism adopted in recent years by the city government in collaboration with different private-public actors. Taking into account risks and opportunities this trend can be expanded into other urban realities for comparative studies with European post-industrial cities through some strategic guidelines for a transitory urban development oriented towards community and well-being.

Include the temporal stage in the masterplan phasing

Several researches have suggested integrating transitional and temporal urbanism into traditional planning (Bishop and Williams 2012; Ziehl et al. 2012) and some European cities are already working in this direction, such as the New London Plan 2018 in which the city of London adopted a temporary use policy and the city of Paris that signed a partnership for the development of transitional occupations with 15 public and private actors.

Transitional urbanism has the capability to quickly unlock the potential of the site, primarily enabling public-space life; conversely, the traditional tool of master-planning is not able to immediately incorporate the current complexity of the city and its social life. To overcome this contradiction and truly benefit from transitory urbanism, conventional planning needs to shift towards a different methodology. Traditionally, a masterplan derives the project guidelines from building specifications, instead of approving a framework plan, the area can be planned starting from its public/open spaces, from its social and ecological qualities and limitations unravelled (Architect 2006).

Transitional urbanism can become an organised stage in the permanent requalification of the site and a mandatory step in the enrichment and programme enhancement of a development project to come (Pradel 2019). If it is adopted as a preliminary phase of a masterplan can instil positive impacts by bringing sustainable practice, like in the Campus MIL undergoing a future repurposing, and can mitigate health problems linked to the site perception through collective participation, binding a territory with its community under the threat of market economy. In other words, it can act as a bridge for social, ecological and economical transition.

Reclaiming of large-scale industrial areas into a set of small-scale temporal interventions

Based on the case study analysis, the immediate conversion/reclaiming of the impermeable system of large-scale industrial areas into a new system of public space requires a set of small-scale temporal interventions and this can lead to diverse advantages. Given the project’s long-term span, the development is more flexible to react to unpredictable market changes without overstepping public and social spaces that can link the past, present and future of the site. Having a single coherent framework for public and social space avoids the health risk of precariousness and uncertainty from disconnected projects across the site.

One example working in this direction is the framework designed by Ghel Architect for the industrial site requalification of the former Carlsberg brewing facility in Copenhagen (Architect 2006). Since the beginning of the rehabilitation, the project has transformed the industrial barriers into a welcoming part of the city centre.

In this narrative, the form of a temporal public space is no longer what should be designed for the future, but what is already there in the site which needs to be unlocked. The aim is to unlock the potential of sites now, rather than in 5 years.

This brings together different figures, such as politicians, architects, activists and citizens, into a multidisciplinary and participatory process across research and design. It is also intended to be a process that cannot happen overnight. It needs time and perseverance from this heterogeneous group in order to gradually instil a different urban identity to embody new categories of public space distinct from the known ones–parks, squares, walks, etc.–that can creatively transform the industrial barriers.

Connectedness via collective urban imaginary

Although transitory urbanism has a short life span in the city’s evolution, how we imagine those spaces is fundamental to conceptualise, anticipate and implement future urban scenarios. Understanding how practice and patterns shape the present human perception has an impact on the future of our individual and collective well-being, and the ability to imagine and anticipate our future starting from temporal practice is necessary in an increasing urban and social complexity. Especially during the last decades, urban austerity and the mainstream proliferation of global practice gradually narrow our urban imagination.

Prototyping new social ideas, and bringing the state and civil society back together in collective dialogue concerning our urban future in terms of social, cultural and health priorities can render alternatives to design ideas as open as possible:

It is also possible to argue that we have not travelled very far at all when it comes to radical visions for urban life. One of the explanations for this is what we might term ‘imaginative lock-in’, i.e. our inability to think beyond relatively normative trajectories when conceiving urban futures and their lifestyles… Pioneers of the future may need to identify apparent voids in existing places and narratives through which we can reimagine the urban. (Dunn 2018)

Conclusion

A temporal urban project can last for an evening, a season or a few years; it can also be periodic or cyclical. Even if the occupancy initiatives are of short or medium duration, as previously pointed out, they always reflect the community’s desire to participate in the right of changing the city and the way it is built in the long term.

If traditional planning aims to adopt transitory urbanism as a step towards site enrichment, the objective is to look at the future as a way to decipher the current urban complexity as a “sphere of the existence of multiplicity, of the possibility of the existence of difference. Such a space is the sphere in which distinct stories coexist, meet up, affect each other, come into conflict or cooperate. This space is not static, not a cross-section through time; it is disrupted, active and generative” (Massey 1999, 272).

Transitional urbanism and its integration into traditional planning and community can limit health problems by ensuring participation and harmonious transition into the development, it remains however problematic to measure the real impacts on the site.

At the heart of the theoretical background and findings of the case studies analysis lie two interconnected and captivating avenues:

Firstly, a collective urban imaginary based on temporal connectivity towards a social, physical, and cultural harmony aiming to bind the context and mitigate the impact of future urban action;

Secondly, a trap for a low-budget permanent urbanism that instils a sense of precariousness and uncertainty in the users. The process and its actors are still very new, and there is a need for more good examples and practices to be provided and tested.

Bibliography

Temporary urbanism covers any initiative on unoccupied land or buildings that aim to revitalise local life before development occurs. In urban policies “temporary uses are often intended to revitalize and unlock a given space’s latent potentialities. It constitutes a way for waiting for a ‘long-lasting transformation’, which can be stimulated precisely by the chosen temporary use. The space-time nexus is the key dimension in which temporary urbanism is manifested.” (Bragaglia and Rossignolo 2021).↩︎

“Transitional urban planning is thus largely put forward today to describe this emerging phenomenon as much as to claim its consideration in planning logics. It defines the temporary occupation of vacant premises or open spaces, public or private, developed or fallow, using light and labile equipment, structures, facilities and supporting economic, leisure, cultural and social activities and now even accommodation. In the vacant building, the articulation of different activities should make it possible to stimulate and attract a diversity of uses and users in a neglected site in order to restore its social value at the heart of the city. One of the main challenges of this approach is to make these unused areas available to the occupants below the market prices of traditional real estate (for example for craftsmen, associations, young companies, artists, precarious or fragile populations, etc.). The term is nevertheless also operational to describe open space development projects awaiting for requalification: vacant land after the demolition of a building and before the construction of a new building, old roads taken part in an urban renewal project of a social housing district, public square undergoing a requalification project, etc. Transitional urban planning then supports participation and consultation processes in the future of the sites. It is thus increasingly considered by its promoters as a step towards enriching and/or enhancing the programmatic value of a future development project. Its vocation is to guide the urban trajectory of the places if the programming is open, that is to say if the functions and uses of the different places are yet to be decided, and if its designers are careful to ensure that it is an experimental laboratory for the future project.” (Pradel 2019).↩︎

“There are more than 25 sq. km. of vacant land in Montreal. This corresponds to the equivalent of about one hundred times the area of Montreal’s Botanical Garden. One third of vacant land in Montreal is public, belonging to the municipal administration, the government of Québec, or to a lesser extent, to the federal government and parapublic corporations” (Montréal and Entremise 2016).↩︎

We define the knowledge economy as production and services based on knowledge-intensive activities that contribute to an accelerated pace of technical and scientific advance, as well as rapid obsolescence (Powell and Snellman 2004).↩︎

This includes those whose work constitutes “directly creative activity,” creative professionals, and others whose work comprises a significant creative component.↩︎

Developed to implement the Heritage Policy, the city of Montreal’s 2017-2022 Heritage Action Plan renews the heritage approach and is structured around four priority avenues: act as an exemplary owner and manager (Agir à titre de propriétaire et gestionnaire exemplaires); ensure the development of local heritage (Assurer la mise en valeur du patrimoine de proximité); support the requalification of the whole identity (Soutenir la requalification d’ensembles identitaires); disseminate knowledge and encourage recognition (Diffuser la connaissance et encourager la reconnaissance) (V. de Montréal 2017a).↩︎