Introduction

Citizen self-organisation in the cities of Mediterranean Europe has become more evident in the period following the 2008 economic crisis. Although the debate in urban and regional planning had already been confronted with decentralization and social mobilization, it was after a season of severe social emergencies caused by the 2008 crisis–first and foremost the housing emergency–that citizen self-organisation regained a more prominent role in the public debate due to its ability to mitigate the dramatic effects of the crisis. Today, in a global situation marked by continuous crises, citizen self-organisation, which is based on mutual support, seems to be one of the few safety nets when thinking of a sustainable present and future.

The case study presented here fits into this scenario of citizen struggle for the creation of a different present: a different city in which urban development is able to strengthen the social and economic local context rather than speculative interests. Can Batlló is a citizen initiative that is the result of the persistent work of its activists and neighbours, which has been able to create an organisational culture capable of managing a space–as immense as Can Batlló–and even communicating its impact. Precisely, these two characteristics–the organisational culture and the continuous monitoring of their work by activists–need to be at the centre of this research in order to study the transformative power of these practices, and inspire other practices of self-organisation in other contexts.

The Can Batlló experience presented here is the result of six months of work and research in the city of Barcelona between August 2019 and February 2020. The research was conducted through in-depth interviews with key stakeholders (Can Batlló activists, policymakers, confrontation with senior researchers), policy document analysis, and participant observation at Can Batlló meetings and activities. This research has already been published in the book The Power of Civic Ecosystems: How community spaces and their networks make our cities more cooperative, fair and resilient (2021), which explores methods and practices for building stronger local civic ecosystems around community spaces in Europe, and has been presented to the International Conference of Urban Commons organised by the University of Turin to share Can Batlló’s experience with other urban common researchers.

Story of an invisible giant

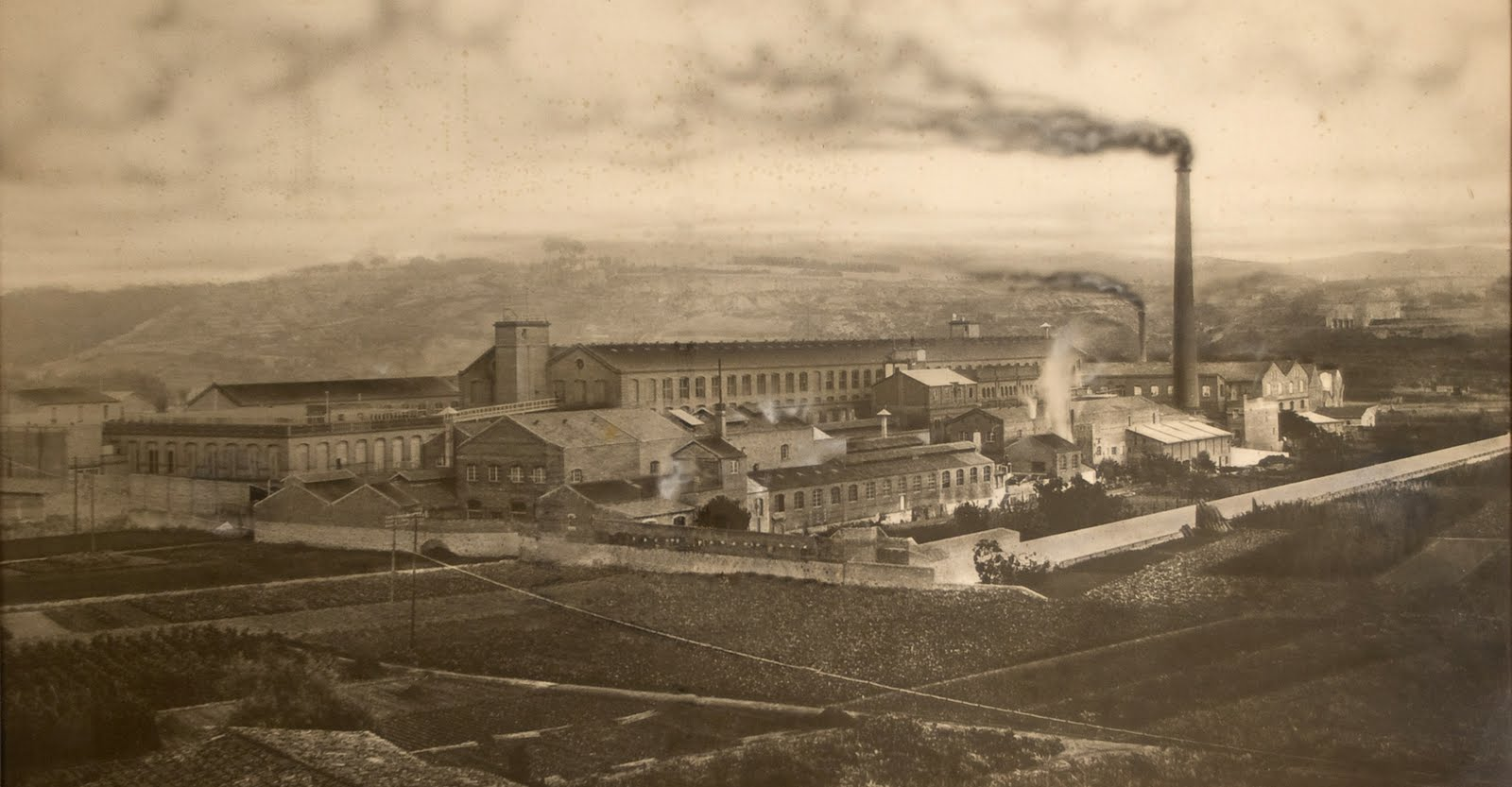

Like other major European cities, Barcelona has a great industrial heritage that can now be reused for a new and different development of its urban life, regenerating spaces, places and communities. The former Can Batlló factory, a post-industrial infrastructure in La Bordeta neighbourhood of the Sants district, is part of this industrial heritage (Lacol and Panóptica 2011). Because of its size of 14 hectares, and of the general interest and dynamics, Can Battló became a site for experimenting with new ways of conceiving and regulating the urban commons. This story is also of significant interest to other cities engaged in bringing urban planning closer to the social activism of its citizens.

Founded as a textile factory in 1880 with the name “Sobrinos de Juan Batlló”, the structure was one of the key economic drivers of Sants’ transformations at the end of the 19th century. In 1976 the Metropolitan General Plan (PGM) defined Can Batlló’s site as an area of public facilities and green spaces. This decision triggered a long fight led by the industrial owners of Can Batlló–the real estate corporation Desarrollos Inmobiliarios Grupo Gaudir, SL–who since the end of the 1990s, in a period of massive building speculation, negotiated several planning changes to obtain greater benefit from the site, in particular from a new project: the construction of several luxury tower houses exploiting the strategic location of the Gran Via, one of Barcelona’s main streets.

When the real estate crisis hit Spain in 2008, investors stopped showing interest. The lack of requalification for such a long time, however, impacted the neighbourhood: since 1976, La Bordeta has been lacking public facilities that were supposed to be built at the Can Batlló site. The district’s indignation led to the constitution of the Platform Can Batlló es pel Barri (Can Batlló is for the neighbourhood), a group of citizens who had always followed the state of (non) progress of the construction. Faced with the immobility of the municipality not complying with any of the project’s deadlines, the Platform decided to issue an ultimatum: if by June 11, 2011, construction work has not started in Can Batlló, the Platform would come and start building the structures they needed themselves1. Thus began a countdown, a media campaign aimed at strengthening and legitimising the Platform with the support of various associations and social movements of Sants and the whole city.

Shortly before the date of entry defined by the citizens, the municipality started to negotiate with the owners for the acquisition of the site also in order to protect the citizens: as the municipality takes over the ownership of the Can Batlló site, citizens occupy a public asset and the municipality can decide to negotiate with them, thus avoiding the eviction from a private property. The first space occupied and reassigned is called “bloc onze” (in memory of the historical date of entry in Can Batlló by the Platform) and marks the beginning of a new phase in the process of rehabilitation and transformation of Can Batlló. Since then, the Platform has been active as a space for reflection and advocacy for the neighbourhood’s surroundings, collectively rethinking its urban transformation. With the subsequent acquisition of the building, the municipality supports the occupation by giving legitimacy to the occupants and returning the space to the neighbourhood with a concession that gives the public administration the responsibility to maintain the building’s external structure while the management of the activities inside Can Batlló are the responsibility of the neighbourhood association, which is Platform Can Batlló es pel Barri.

An enabling system

Since 2011, the inhabitants of La Bordeta involved in the regeneration of Can Batlló have decided to organise all their activities with a horizontal, inclusive and transparent monthly assembly composed of working committees. The assembly decides all the activities, uses and plans for the sustainability of the space. Inside Can Batlló, almost 400 citizens have been working cooperatively and voluntarily to meet the social needs of the neighbourhood, renovating the spaces collectively, refurbishing and making the space available to everyone without any distinctions.

The General Assembly is held on the last Wednesday of each month and is where main decisions are taken. All committees and projects are involved and invited to participate, committees are more organisational structures while projects are more singular activities. The commissions and projects are divided into 4 major groups:

Internal structure: made of the following committees: Secretariat and Reception for the Neighbourhood and Visitors Dissemination, Strategy, Negotiation, Economy, Space Design; Infrastructures.

Arts and crafts: the Arts Can Batlló committee plus the following projects: Carpentry, Collective Printing, Mobility, Audiovisual Laboratory of Can Batlló AvLabCB, Espai Eines (School of Trades), Beer Workshop, Sewing Workshop.

Education and documentation: composed by the following projects: Josep Pons Popular Library, La Fondona, Social Movements Documentation Center, Arcadia School.

Culture and leisure: the Activities committee plus the following projects: Meeting space, Bar, La Nau, Children’s and family space, Community Orchards and Gardens, Musical Creation Space, Climbing wall, Performing arts and circus training space, La Garrofera de Sants, La Borda, Coopolis.

Open meetings are often held on specific topics such as economics, space improvements, and discussions on the urban transformation of the entire site. The General Assembly has also discussed, planned, and followed for more than two years the renovation of the bloc onze, the first building financed by the municipality, through collective work sessions.

The first space to be set up was the Josep Pons popular library. Later, a bar and meeting space, an auditorium, a climbing gym and several multifunctional rooms for activities and workshops were renovated. As the working group and the interest grew, the Platform also managed to recover more spaces within the same complex for other community projects and always in the same way: the municipality acquired the spaces one by one and entrusted their management to the Platform. Over the years, other locations were transformed and new uses were established: a repair shop, a carpentry shop, a collective printing shop, a documentation centre, a space for families, a space for the arts, and a circus arts gym. In 2013, together with the new street Carrer de l’Onze de Juny de 2011, which was opened to stretch across the site from one end to the other, the first community garden (50m2) was inaugurated.

The Platform Can Batlló es pel Barri worked and questioned the previous urban planning project for the area and worked on new proposals that revise the transformation of Can Batlló. Since its beginning, the Platform adjusted and improved the Metropolitan General Plan of Can Batlló-Magòria.

Self-management, collaboration in general activities, maintenance and good functioning of the project are the essential commitments for all people and groups joining the “bloc onze”. The Assembly decides on the self-financing methods that are allowed internally according to the following guiding criteria: projects or individuals who contribute with money cannot run activities that are against the principles of the “bloc onze” and cannot endanger its independence. Can Batlló is engaged to move towards economic self-sufficiency at all levels of the organisation, within the commissions, working groups and the General Assembly. It is everyone’s commitment to work towards this goal which creates processes of independence from grant funding and/or public funds. People and groups using the spaces for activities must contribute to the community with a social and/or economic return. The path towards economic self-sufficiency does not derive from a position against the municipality but from an entrepreneurial vocation embedded in the history of the place. Multifunctionality, activism and periodic change of activities make this place a new generator of economic and social life in the Sants district.

A new legal and conceptual framework

The internal organisation and its inhabitants’ social activism transformed Can Batlló into an enabling system. In this process, the municipal administration played a non-secondary role, and was able to adopt new tools for the co-management of urban commons. These new tools are the result of a significant paradigm shift in the way the public sector is conceived.

In 2016, the city council led by Barcelona en Comù (a political party including several social activists aiming to bring citizens closer to political life in an active way) started a process of defining the rules of co-management of publicly owned spaces together with the Network of Community Spaces of Barcelona, the XEC-Xarxa d’Espais Comunitaris. The Network had long been asking for parameters that could go beyond the dominant market logic and for the redefinition of ways to measure activities within the co-managed spaces. Thus, a project was initiated to establish a new conceptual and normative framework based on a definition of urban commons started. A systemic approach to the city’s facilities was also adopted, an approach in which libraries can also host social services, meeting other needs of the surrounding area. Moreover, the municipality was beginning to take on a new position and a new language: goods and services, which were once in the hands of the “public” can now be managed as “commons”. The city council wanted to promote processes such as Can Batlló, where local communities are able to self-organize and make a positive social impact by working for a common good. As a result, this change led to the definition of the Programa de patrimoni ciutadà d’ús i gestió comunitàries, the Citizens Assets Programme.

Within this new programme, the concession of more than 13,000 square metres to the Can Batlló neighbours’ association represents another important innovation: a politically risky decision, a process of innovation within the local administration that pushed technicians to go beyond the comfort zone of their usual office work. For the first time, an urban planning concession has been given in the favour of a self-managed non-profit entity considering that the community project of Can Batlló constitutes an important social benefit for the city of Barcelona, measured and monitored according to new administrative tools: the community balance and social return.

Community Balance

Within the Barcelona City Council, a cultural change has been taking place in the last five years. Planning to go further than what was previously done in the carta de participació ciutadana (citizen participation charter) (2002) and the gestió cívica (civic management) (2015) schemes, the city council began to understand that the benefit of a public structure managed by the neighbourhood is much more than just economic. The Barcelona Network of Community Spaces-Xarxa d’Espais Comunitarios was already familiar with this concept: According to them, a community project has a greater social benefit, is capable of stimulating active citizenship and is deeply rooted in the territory.

The cultural change promoted by the Municipality and the XEC led to internal disagreements among some citizen groups, a contrast between those who wanted to remain rooted in the old civic management model and those who wanted to adopt a communitarian vision. The XEC also felt very close to realities that were still alien to this network of spaces, such as Can Batlló. It was necessary to establish what the characteristics of community management were in order to understand what civic centres that promote a communitarian vision had in common and also to understand how to improve them.

It was necessary to go beyond the logic of simple city management, regulated by a contract with the municipality, an annual budget review, 3+1 or 2+2 year renewal formulas, and a performative request by the municipality through the use of quantitative and productive parameters (number of workshops and people involved). Until that point, the dialogue between civic centre managers and the municipality was solely based on an annual budget and on a report of the activities carried out with all the numbers involved. Starting from the assumption that there is no point in producing and participating in the management of civic spaces if it is not possible to transform the context in which one works, XEC was already asking (since 2011) for a new set of indicators that would allow to better evaluate the work of communities in order to improve on some points: social cohesion, gender equality, sustainability, democratic participation among others. An evaluation study similar to the Social Balance (Balanç Social) which was already used by the members of the Catalan Solidarity Economy Network2 (XES-Xarxa d’Economia Solidària).

Elements of the Community Balance

The Community Balance wants to systematically and objectively evaluate four main characteristics of every socially responsible community space: democracy, equality, environmental and social responsibility, and quality of work. The tool co-designed by XEC together with the Municipality and the cooperative La Hidra is inspired by the tool used in the world of solidarity economy and uses the same web platform (open code) for its formulation. This is still under development, as a first version was made in 2018 and a second one in 2019. For now, a list of 14 associations has been “balanced” to test and improve the questions and parameters designed so far. The set of indicators developed so far can be grouped into the following 4 areas of work:

Rooting to the context: the orientation of the project towards the actual needs of the territory (neighbourhood) and the extent to which it manages to coordinate itself in the production of activities with other realities of the territory: socio-cultural, productive or commercial and institutional associations (schools, municipal services, etc.). The relationship with existing networks within the same territory or sector is also taken into account here.

Social impact and social return: the project’s response to community interest and/or orientation towards the common good, as well as social impact and positive externalities and whether there are beneficiaries outside the project.

Internal democracy and participation: the internal governance of projects must be as democratic as possible. Participation channels must be designed to promote the activation of users and neighbours in producing space activities. The degree of transparency in the management of the spaces and the existence or non-existence of a code of ethics, and standards of conduct, are also taken into account.

Care for people and the environment: a commitment to sustainable working conditions, and the promotion of diversity. Gender equality is measured here, including the adoption of a gender perspective in the definition of the objectives set. Similarly, it values the commitment to environmental sustainability, with energy savings or the use of renewable energy sources. Finally, the economic sustainability and self-sufficiency of the project are also assessed.

A special public-community relationship

Can Batlló’s experience demonstrates the importance of both community networks, which act as intermediary bodies, and the involvement of technicians and citizens to innovate in local government. A new regulatory framework and new tools for measuring and accompanying projects oriented towards the common good are the result of a (not easy) collaboration between two different spheres (activists and technical administrators), who often find themselves in a conflictual relationship. However, the case of Can Batlló does not exhaust and does not resolve the tensions that will continue to exist, both among activists and technicians, even within a government that fully supports the cause of the common good. The challenge now is to demonstrate that the regeneration of Can Batlló is a bet won by all, especially by those who have devoted the most time to its development.

A final result will be defined above all by a correct definition and use of tools such as community balance and social return. It is necessary to prevent community balance from becoming one of the many ways in which the local government can control community projects. In order to accomplish this, it is necessary to recognize the political relevance of these tools, to call for their use and to demand a different role for the municipality, which must act as a permanent facilitator, promoting these community processes, without forgetting that there are no commons without commoning, and therefore without community. The effort made so far highlights the commitment of the city of Barcelona in order to change the way it conceives “the public sphere”, including for future governments, which creates internal tensions within the administration. It is also worth mentioning the effort made by Can Batlló’s neighbours in forming an association to facilitate communication with the public administration. Community, co-design and communication have been the key elements in making Can Batlló a remarkable case in the field of community-led urban regeneration studies.

Bibliography

“Si al juny de 2011 les màquines excavadores no estan en el recinte de Can Batlló, entrarem nosaltres i començarem a construir l’espai públic i equipaments que necessitem” (if there are no excavators at the Can Batlló facilities, we will enter and start building the public space and the equipment we need). Available at https://canbatllo.org/can-batllo/#historia.↩︎

The Catalan Solidarity Economy Network is an organisation with more than 300 members. It defends an economic system that respects people, the environment and territories and functions according to democratic criteria of horizontality, transparency, equity and participation.↩︎

See https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/participaciociutadana/en/noticia/approval-to-grant-the-use-of-can-batllo-to-a-self-managed-community-association_790268.↩︎

Social Return

An urban planning concession such as the one allocated to Can Batlló is normally granted to private and large construction companies because a municipality must always “justify” the concession with an immediate monetary return or a future real estate return: in this case, the building is returned to the municipality at the end of the concession. On the contrary, the Can Batlló Neighbours’ Association wanted to obtain the management of the space through an urban planning concession within the new Citizens Assets Programme because this type of agreement could guarantee them more freedom within the site. The concession obtained for a period of 30 years, expandable to 10 or 20 more, allows the association to plan the activities with great stability and to better plan for the common good.

The initial media interest aroused and the work carried out over the years by the Platform led the neighbours of Can Batlló to engage in a productive dialogue with the administration, succeeding in involving several working groups and municipal technicians (especially in the areas of heritage and participation). The challenge, once the political will was found, was to try to “hack” the system that regulated concessions and find a way to justify the concession even without an immediate monetary return.

The valorisation of the work done by all the volunteers of the Platform over the years within Can Batlló was expedient to justify the concession. The social return generated by Can Batlló does not have a monetary value in itself but trying to “translate” into economic terms the time spent by its volunteers (in recovering the whole structure and offering the services that would otherwise be offered by a civic centre of the municipality) was the only way to involve the municipality and obtain the concession.

In order to measure economically the work done by the community, two evaluation methods were adopted for a more objective comparison. The first method involves the monetary valuation of the unpaid work hours of volunteers and activists. The second method involves the monetary valuation of the cost that the administration would have to sustain if it decides to take over the activities and services currently active in Can Batlló. It is thus possible to estimate how much the city of Barcelona benefited monetarily from the self-managed social activism of Can Batlló’s neighbours.

Taking into account the total number of hours worked by the volunteers between 2012 and 2017, it is possible to make an overall assessment of the historical cost of Can Batlló. Counting the hours of volunteering since the beginning of the regeneration process of Can Batlló, including the hours dedicated to space development (construction), community management (assemblies and participation spaces), group activities (projects and commissions), cleaning its premises, festival spaces and maintaining the spaces, the Barcelona City Council estimates that for every euro invested in Can Batlló, the project generates a return for the city of over €53.

The evaluation carried out by the Municipality of Barcelona justifies the investment already made in Can Batlló to recover the building and give legitimacy to the neighbours’ association. The calculation of the Social Return is thus able to “hack” the urban planning concession.

The first method used in this case turns out to be the one most in line with the recommendations of the International Labour Organisation regarding the measurement of volunteer work (2011): this method corresponds to the “full replacement cost method” in which volunteer work is attributed a cost equal to the remuneration needed to hire a worker active in the market to perform the same services offered by volunteers. This type of measurement attributes to volunteer work a quality not inferior to that of a professional in the sector and is, therefore, more in line with the thinking of the community volunteers of Can Batlló.

The Can Batlló volunteers managed to coordinate themselves over time and to have a history database of the hours spent because they think this is a good way to communicate the value of their activity and to better manage their work. The time spent and the result of the work of space maintenance have for them a value that goes beyond the economic measure made only to justify the concession–the community of Can Batlló continues to count the hours spent on each project even if the concession has already been reached. Some of them even like to play with numbers, which they consider as additional data to get more information about the work done.